Events

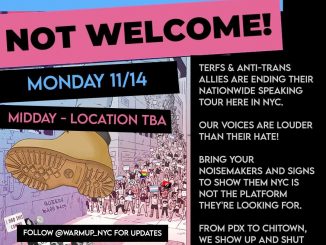

New York City: Transphobes not welcome! Nov. 14

TERFS & anti-trans allies are ending their nationwide speaking tour here in NYC. But our voices are louder than their hate! NYC, TELL EM: TRANSPHOBES NOT WELCOME! Monday 11/14, midday Exact time + location TBA […]