On Jan. 13, the Tribal Council of Red Lake Nation voted unanimously to restrict ICE and other federal immigration agents from entering Red Lake lands without a court order signed by a judge with jurisdiction. The resolution became public Jan. 28, as tribal leaders warned that federal agents were already “moving north.”

Under the new protocol, ICE must obtain a valid court order, present it to the Red Lake Department of Public Safety director, submit to a Red Lake officer escort at all times, and leave immediately after the order is served.

The council did not soften its language. Members said they were “ashamed and disgusted at the obvious violations of constitutional rights that are routinely being directed at United States citizens by ICE officers.”

Chair Darrell Seki Sr. also notified Minnesota’s congressional delegation that tribal officials had been told federal officers would soon “turn their sights north,” after ICE agents apprehended a member of the Leech Lake Band near Walker in northern Minnesota.

Red Lake’s action carries particular force because it is Minnesota’s only “closed reservation” — its land was never allotted, remains held in common, and the tribe retains authority over who may enter. Red Lake is also exempt from Public Law 280, meaning state courts have no jurisdiction on tribal lands. Together, these conditions preserve Red Lake’s sovereign control over its territory.

The impact reaches far beyond the reservation. Tribal officials estimate roughly 8,000 Red Lake people live in Minneapolis, placing thousands of Indigenous community members inside ICE’s expanding enforcement zone.

From Bdóte to Minneapolis: detention returns to familiar ground

Red Lake’s move comes amid a wave of Indigenous detentions in Minneapolis.

In early January, four tribal members were detained under a bridge near the Little Earth housing complex in East Phillips. Three were transferred to an ICE facility at Fort Snelling — a site Dakota people remember as a concentration camp at Bdóte, where the U.S. military imprisoned about 1,700 Dakota in 1862 as part of a broader campaign of genocide and forced removal. Families were held there behind military lines, exposed to disease and hunger, before being driven from their homelands into exile.

For Dakota communities, Fort Snelling is not a historic landmark. It is a site of mass detention. Families were confined there while the U.S. government carried out mass executions of Dakota men, before survivors were expelled from their homelands into exile. That same ground is now being used again to cage Indigenous people.

President Frank Star Comes Out of the Oglala Sioux Tribe confirmed that three of the detainees were taken to Fort Snelling.

“The irony is not lost on us,” he said. “Lakota citizens who are reported to be held at Fort Snelling — a site forever tied to the Dakota 38+2 — underscores why treaty obligations and federal accountability matter.”

The Dakota 38+2 refers to the 38 Dakota men publicly hanged by the U.S. government in Mankato on Dec. 26, 1862 — the largest mass execution in U.S. history — and two additional Dakota leaders, Sakpedan and Wakan Ozanzan, who were executed at Fort Snelling in 1864.

When the tribe requested information about its detained people, federal officials said it would need to enter an “immigration agreement” with ICE. The tribe refused.

“We will not enter an agreement that would authorize, or make it easier for, ICE or Homeland Security to come onto our tribal homeland,” Star Comes Out said.

One detainee has since been released.

Another case involves Jose Roberto Ramirez, a 20-year-old man of Red Lake Anishinaabe descent who was detained after ICE agents reportedly punched him during his arrest. His mother brought his passport and birth certificate to a federal building in Minneapolis, but was turned away.

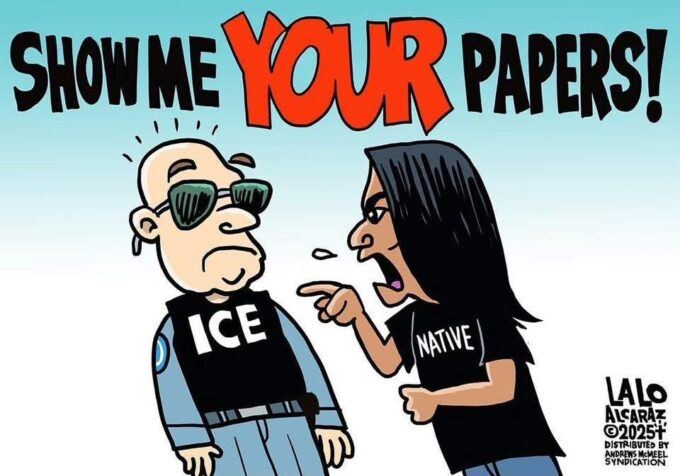

Legal advocates note that ICE has no jurisdiction over Indigenous people in immigration matters. Federal law imposed U.S. nationality on tribal people in 1924, but treaties recognize Native nations as self-governing. As Star Comes Out wrote in a memo to members, “Tribal people are not aliens.”

Yet on the ground, those legal facts are being overridden by armed enforcement.

In Minneapolis, ICE is operating as a roaming detention force — stopping Indigenous people in public space, demanding documents, and transferring people into federal custody.

This is urban removal: surveillance first, seizure second.

Communities organize as ICE expands north

Indigenous communities across Minnesota have begun building rapid-response networks to intervene when ICE appears. Rachel Dionne-Thunder, co-founder of the Indigenous Protector Movement, narrowly avoided arrest Jan. 9 after neighbors and organizers converged when agents surrounded her vehicle.

Red Lake officials say such organizing has become necessary because ICE tactics are widening geographically and intensifying operationally. The Tribal Council cited reports of agents moving north out of the Twin Cities, signaling a broader regional push.

Similar confrontations with federal immigration agents have occurred in other states. In November, Indigenous actress Elaine Miles, a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Oregon, said ICE agents in Washington state questioned the legitimacy of her tribal identification, calling it “fake” before allowing her to go.

From Minneapolis streets to reservation borders, the first peoples of the Americas are being pulled into an enforcement dragnet that treats them as deportable bodies.

Join the Struggle-La Lucha Telegram channel