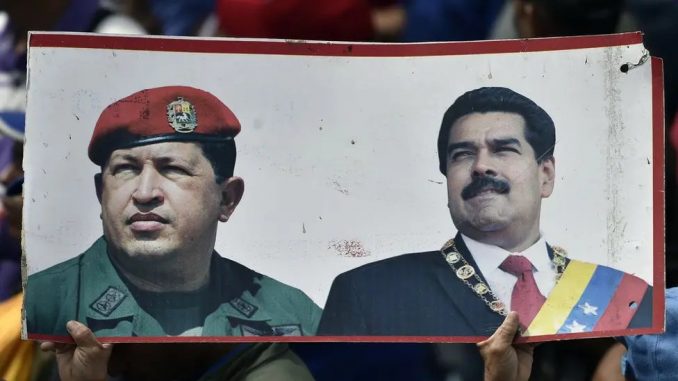

The political durability of the Bolivarian Revolution is grounded in material gains won by the working class and the poor. It is anchored in a concrete social contract that transforms Venezuela’s oil wealth into improvements in daily life and reshapes the country’s political landscape in the process. Since Hugo Chávez’s election in 1998, the redistribution of surplus has forged and sustained a mass base rooted not in symbolism or ideology, but in tangible changes to living conditions that give Chavismo its popular legitimacy.

Oil revenues and working-class gains

Central to this shift was the reassertion of state control over Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). Chávez’s government broke the autonomy of the oil technocracy and redirected oil revenues toward working-class communities long excluded from national wealth.

Oil income is treated not as an abstract macroeconomic lever, but as a social resource. Through price controls, direct state provisioning, and heavy subsidies, the state intervenes across daily life — food, housing, health care, education, and public services — while expanded social spending and labor protections allow workers to win higher wages, improved benefits, and greater economic security.

The results were neither marginal nor symbolic. In less than a decade, poverty was nearly cut in half, while extreme poverty fell by more than two-thirds. University enrollment more than doubled, unemployment was reduced by half, and child malnutrition declined sharply. Income inequality fell so sharply that by 2012 Venezuela had become the most economically equal country in Latin America.

These were not isolated policy wins; they were the cumulative effects of a redistributionist model funded by oil revenues and enforced through political struggle against domestic capital and foreign imperialist interests.

This redistribution forms the material foundation of Chavismo’s working-class base. It does not represent a departure from Venezuela’s economic structure, but a decisive intervention into it. Venezuela is already an oil economy; the political question is whether that wealth flows upward to capital or is redirected toward social reproduction.

The external shock: oil prices collapse

The rupture comes from outside that social contract. When Nicolás Maduro was elected president following Chávez’s death in March 2013, global oil prices soon collapsed. In 2014, prices fell by roughly half, beginning a decline that reached nearly 70% by early 2016. State revenues were slashed in a matter of months. The fiscal capacity that had sustained subsidies, social programs, and price controls was sharply reduced, placing immense strain on the gains achieved in the previous decade.

Had this revenue shock been the full extent of Venezuela’s difficulties, recovery might have followed the eventual rebound in oil prices. Instead, the downturn was locked in place by escalating U.S. sanctions.

Imperialist sanctions and economic warfare

Beginning in 2017, Washington imposed measures that went far beyond diplomatic pressure. Venezuelan oil sales were blocked, state assets were frozen, and the government was prohibited from refinancing debt or accessing international credit. It was open economic warfare.

The United States stripped Venezuela of control over key offshore assets, including U.S.-based refineries, cutting off access to critical sources of income.

The timing was decisive. As global oil prices recovered, Venezuela’s production remained choked off — not by geology or technical capacity, but by financial and commercial strangulation. Sanctions foreclosed any path to stabilization, let alone renewed redistribution. What began as a revenue shock became a sustained economic siege.

The human cost of siege

The human cost of this siege was severe. Between 2014 and 2021, Venezuela’s economy contracted by more than 80%. Hyperinflation destroyed wages entirely, peaking at over 130,000% in 2018. Poverty surged across the population as access to food, medicine, and basic services deteriorated under conditions of blockade.

This immiseration produced one of the largest migrations in modern Latin American history. Roughly 7.7 million people — about a quarter of the population — were forced to leave the country in search of survival. This was not a voluntary exodus driven by consumer aspirations or political disaffection. It was the physical displacement of a working class whose material supports were systematically dismantled.

A working-class base under strain, not defeated

Venezuela’s economic difficulties are often narrated as a morality tale about mismanagement or ideology. That framing obscures the underlying political economy. The Bolivarian Revolution achieved real gains for working people by redirecting oil revenues away from capital and imperialist control. The later economic deterioration was driven not by redistribution, but by imperialist intervention following the 2014 oil price shock.

What was damaged was not political legitimacy or popular consent, but the material infrastructure that sustains social reproduction under a hostile global order. The working-class base built through redistribution remains in place, even as sanctions and blockade grind down living conditions.

Join the Struggle-La Lucha Telegram channel