Part 1: How China fought to build a new society

China’s rise as the world’s major industrial center is reshaping the global economy. What was once concentrated in the United States, Western Europe, and Japan has shifted toward China, where hundreds of millions of workers now produce the machinery, electronics, and manufactured goods that underpin everyday life around the world.

This shift disrupts the underlying economic structure of imperialism that has governed the world capitalist system for more than a century — where dominance in the most advanced sectors of production has provided the capitalist powers with a decisive material advantage.

China’s lifting of more than 800 million people out of extreme poverty since the late 1970s has been the largest global reduction in economic inequality in modern history. It’s a victory of socialism.

The contrast with the United States and other imperialist powers is stark. As China eliminated extreme poverty, the U.S. saw homelessness rise, hunger worsen, wages stagnate for almost two decades, and millions pushed into unstable, insecure living conditions despite enormous national wealth.

Deep poverty is a significant and persistent issue in the U.S. Approximately 5.0% of the population lives in deep poverty, and 40% are poor or low-income. The difference is structural: one system mobilizes around human need, the other around corporate profit.

China’s role in the world today cannot be separated from the long course of its revolution: the victory over foreign domination in 1949; the first decades of socialist construction; the Cultural Revolution to block the rise of a new privileged stratum; and the post-1978 turn that opened space for private capital and created the mixed system whose contradictions still shape China’s development.

Socialism means social ownership of the means of production and an economy organized to meet people’s needs rather than maximize profit. That is the core of the struggle.

Development under capitalism and socialism follows two very different paths. Capitalism expands through its own internal motion, driven by competition and profit. It can operate under almost any political form — parliamentary democracy, military rule, even open fascism. Its crises are periodic and unavoidable: when the system breaks down, production collapses, jobs vanish, and living conditions for the most exploited layers take the hardest hit. Yet capitalism rebuilds itself on the same foundations, preparing the ground for the next crisis.

Socialist development is different. It does not arise spontaneously. It has to be built — through planning, public ownership, and a workers’ state led by a revolutionary party. Without the leadership of a party firmly anchored in socialized property and committed to advancing socialist construction, the system does not simply stall. It begins to break down and open the door to capitalist restoration, often in conditions marked by intense struggle.

China is a workers’ state (that’s what Lenin called the Soviet Union) that retains the core instruments of proletarian power: state ownership of key sectors of industry, technology and banking; central planning capacity; Communist Party control over the military and political system. But the market policies introduced from the late 1970s onward left their mark. They created a large private sector, pushed profit-driven practices deep into the economy, widened income gaps, and fostered a privileged layer whose outlook leans toward capitalism. Under Xi, the state has moved to check these tendencies and curb corruption, but the pressures built up over those earlier decades have not simply disappeared. They continue to shape the ground on which socialist construction has to advance.

To understand China today means looking at how a workers’ state was built, how it developed under pressure, and how it faced the threats of imperialism — in China and in the Soviet Union.

The revolution begins: 1949 and after

Every revolution inherits the contradictions of the society it destroys. When the People’s Liberation Army entered Beijing in 1949, China did not become socialist overnight. It became a workers’ and peasants’ government leading a country devastated by foreign occupation, warlordism, and deep underdevelopment. The new state united workers, peasants, sections of the national bourgeoisie, and petty-bourgeois layers in a common front against imperialism and feudal remnants. Socialist transformation had begun, but it was far from complete.

Mao and the Communist Party accurately described the new state as a “people’s democratic dictatorship” — a workers’ and peasants’ republic with allied classes — not yet socialism. This was not a semantic distinction. It reflected the real class composition of the new state. Many private owners — from larger national capitalists to small shopkeepers and richer peasants — remained in place. Commodity production continued, and many capitalists were compensated rather than expropriated.

Foreign observers grasped the ambiguity. Owen Lattimore, Washington’s China expert, argued that the new regime was not a “second Soviet Union,” while some liberals insisted that China’s transformation resembled earlier peasant rebellions — another Li Zicheng moment in which a dynasty collapses but the underlying order persists. They misunderstood the character of the Chinese Revolution but recognized something real: the danger that, without a deeper socialist transformation, the old relations could reassert themselves.

The Chinese Communists understood this danger better than anyone. They knew that overthrowing the landlords and the bourgeois strata that served foreign capital was only the first step. The revolution had to keep advancing — through technological modernization, national planning, and the broadest mass participation. That meant a party capable of educating, organizing, and unifying the people, and fighting for their active, conscious involvement in the work of socialist construction. Without this second step, China could sink back into dependency, deepening economic divisions, and imperialist subordination.

The unresolved class contradictions of the early People’s Republic of China gradually reappeared inside the Party itself. The survival of commodity relations, the persistence of privileged strata, and the pressures of uneven development created fertile ground for new bourgeois tendencies to emerge within the administrative apparatus.

By the early 1960s, the Communist Party had become the battleground. The administrative layers of the state were solidifying into entrenched privilege. Officials with specialized knowledge and control over resources formed a stratum increasingly separated from the working class. Inside the Party, rightist forces led by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping pushed for policies that increased economic inequality and reopened channels to capitalist relations. Khrushchev’s post-1956 course in the Soviet Union emboldened these elements, offering a model for retreat under the banner of “modernization.”

Mao recognized that the danger of restoration did not come only from outside pressures — from imperialist powers like the United States and Japan — but from within the socialist state itself. Bureaucratic privilege, widening economic inequalities, and the growing distance between officials and the masses prepared the soil for new exploitative tendencies to take root.

It was this danger — more than any economic difficulties — that set the stage for the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution and framed how China faced the already deepening crisis in its alliance with the Soviet Union.

These internal tensions met an external crisis that helped bring them to a breaking point.

The Sino-Soviet split and the imperialist wedge

To understand how relations between the USSR and the People’s Republic of China unraveled so sharply, it helps to look back at Lenin’s last political writings. Long before Mao and Khrushchev exchanged polemics, Lenin warned that the young Soviet state carried within it the dangers of “Great-Russian chauvinism”—a legacy of the old empire that could distort relations between socialist nations if not fought relentlessly. Those warnings became one of the buried fault lines that later widened into the Sino-Soviet split.

Lenin insisted that a socialist union could not be held together by administrative command or by the habits of an old ruling nationality. The new union had to be built on equal footing among formerly oppressed peoples. In the struggle over how to form the USSR in 1922, Lenin criticized Stalin’s plan to fold the non-Russian republics into the existing Russian federation. He argued instead for a voluntary union of equal republics, with full recognition of the right of oppressed nations to shape their own development. Anything less, he warned, would reproduce the arrogance of the old empire inside the workers’ state itself.

These were not abstract concerns. Lenin spoke openly about “imperialist attitudes” surviving in the mindset of officials who, though members of a revolutionary party, still carried the habits of the old bureaucracy. He cautioned that if the Soviet leadership treated smaller nations dismissively, it would undermine the credibility of socialist internationalism—especially in Asia, where national liberation movements were awakening.

These insights help explain the later difficulties between the USSR and China. The Chinese revolution arose in a country battered by foreign occupation and internal stagnation. Sensitivity to national dignity came from lived experience with imperialist domination, not from rhetoric. When Soviet leaders, especially under Stalin, dealt with the Chinese Party in a paternalistic or heavy-handed way, it struck at precisely the danger Lenin had warned about.

During the battle between China’s Communists and the Kuomintang after World War II — Stalin’s approach reflected a mixture of caution and diplomatic maneuvering. He doubted the Chinese Communist Party could win and pressured it to compromise with Chiang Kai-shek. Even after victory, Stalin initially hesitated to treat the Chinese revolution as a full partner. The Chinese understood these actions as great-power behavior.

As Chinese leaders later said, “Stalin displayed certain great-nation chauvinist tendencies in relations.” Yet despite these frictions, the 1949 revolution produced real unity. Soviet aid during China’s early socialist construction was enormous. Chinese leaders publicly praised Stalin, stressing the “unbreakable friendship” between the two socialist states.

The relationship began to fray only after Stalin’s death. Khrushchev’s policies combined partial criticism of Stalin’s excesses with a turn toward “peaceful coexistence” and diplomatic conciliation with the imperialist powers. For a country that had faced U.S. forces in Korea and U.S. pressure over Taiwan, Khrushchev’s shift appeared to play down the threat of imperialism. Still, the Chinese did not question the socialist character of the USSR; they saw the issue as a wrong line within a sister party in the socialist camp.

The deeper break came when Moscow acted unilaterally in ways that touched national dignity—just as Lenin had warned. The abrupt withdrawal of Soviet aid in 1960, the nuclear test ban negotiated behind China’s back, and Soviet maneuvering with India during border tensions all confirmed for the Chinese that they were not being treated as equals. What began as ideological disagreement came to feel more and more like China being talked down to.

Inside China, these tensions developed in parallel with the Cultural Revolution, which intensified criticism of bureaucratic privilege — in China and in the Soviet Union alike. Out of this heated atmosphere came new labels: “restored capitalism,” “social imperialism.” These terms expressed genuine anger at chauvinist behavior by Soviet leaders but did not reflect the material reality of the USSR, which remained a workers’ state with socialist property relations born of the October Revolution. Lenin’s distinction between leadership errors and the class character of the state was lost in the storm.

By the late 1960s, the conflict spiraled into border clashes, giving imperialism an opening it had long sought. The tragedy is that the split was not a clash between two social systems, but the triumph of the dangers Lenin warned about: bureaucratic narrowness, the great-nation chauvinist habits the Chinese had long criticized, and the ongoing pull of old privileged hierarchies.

The Cultural Revolution: A mass struggle to defend the socialist gains

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966–76) was launched to confront the same danger that had already overtaken the Soviet Union under Khrushchev — the rise of a privileged layer inside the socialist system that could steer the state back toward capitalism. This danger did not come from old landlords or foreign invaders alone. It came from the social pressures of the world capitalist system itself, which continued to assert influence through the uneven economic conditions, habits, and bureaucratic tendencies left over from class society. Mao believed that unless these pressures were confronted directly, China would face the same retreat.

The response was to turn to the masses — the only force capable of answering a struggle that had shifted onto political ground inside the state. Workers, peasants, and especially students were called on to challenge officials whose authority was separating them from the people and bending the revolution toward a new hierarchy. This was not a matter of discipline or administrative reform. It was class struggle, unfolding within the institutions that had been created to abolish class rule.

The confrontation with Liu Shaoqi made this clear. Liu did not stand for a single mistaken viewpoint; he expressed a political tendency that grows whenever a privileged stratum develops inside a socialist state. This tendency does not have to call itself capitalist. It shows itself through the defense of special advantages, a reliance on bureaucratic authority over mass initiative, and a pull toward the methods and values of the old society. The struggle against Liu’s faction was, in reality, a struggle over whether this privileged stratum would consolidate enough influence to steer the revolution toward capitalist restoration.

The Cultural Revolution’s greatest accomplishment was that it shifted the balance of power back toward the masses. Their participation reasserted that only the people can determine the direction of socialist development. It cut into the growing influence of a privileged layer that was distancing itself from the people and stopped those pushing for a turn away from socialism from gaining ground.

This follows what Engels observed about earlier revolutions: the first victory overturns the old ruling class. The next struggle arises inside the new society itself, against conservative forces that try to revive elements of the old order in new forms. China’s 1949 Revolution established a workers’ and peasants’ state, but its gains were not guaranteed. The Cultural Revolution acted as this second wave — the effort required to prevent an emerging stratum of officials from gaining the authority to reverse the accomplishments of the first wave.

The achievements of the Maoist period — the expansion of collective industry, the rise of social equality, the mass mobilization of working people in public life — were defended because millions intervened at a decisive moment. Their actions prevented privileged forces within the state from consolidating enough power to turn China back toward capitalism. For a crucial period, the Cultural Revolution stopped the gains of 1949 from being rolled back.

Because the gains of 1949 were defended at a decisive moment, China could move forward with the long-term work of socialist development. What came next was not a pause in the revolution but its extension into the fields, factories, and social institutions that shaped daily life.

Mao’s economic record revisited

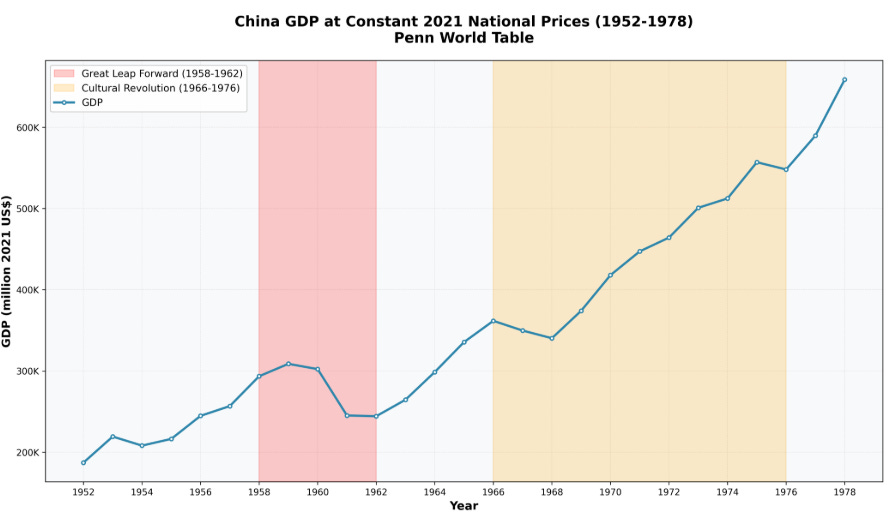

China’s economic record from 1949 to 1976 is often portrayed in Western accounts as stagnation and failure. The story has been repeated so widely in corporate media and academic writing that it’s taken as fact. The actual record shows something different: a period of extraordinary change under conditions of imperialist pressure and deep poverty.

In the first decades after 1949, China’s industrial growth often approached the pace of the early Soviet Union — one of the only countries to industrialize so rapidly in the 20th century. For a nation emerging from colonial underdevelopment, this was an exceptional achievement.

Entire branches of heavy industry were created from nothing. Life expectancy nearly doubled. Illiteracy fell at a rate unmatched in much of the developing world. Rural healthcare, education, electrification, irrigation, and basic infrastructure expanded at a speed that capitalist governments had never achieved over centuries of rule. By the mid-1970s, China had full employment even as many countries in the global South faced recession, structural adjustment, and deepening dependency.

These advances did not arise from “catch-up capitalism.” They were the product of a socialist state mobilizing millions through collective planning, mass campaigns, and the political energy released by a revolution that had overturned feudal landlords and foreign domination.

The Mao-era period of socialist construction built the industrial, scientific, and social base for China’s later development. Without the foundations created through collectivization, cooperative agriculture, public ownership, and mass participation, there would have been no platform for the policies that came in the late 20th century.

None of this suggests the era was without contradictions or setbacks. The Great Leap Forward faced severe difficulties and produced major crises. The Cultural Revolution was a turbulent attempt to confront rising privilege. The revolution was unfolding in one of the poorest countries on earth, ringed by hostile imperialist powers, cut off from global markets, and lacking a developed administrative and technical layer. Under those conditions, sharp turns and mistakes were unavoidable.

The dominant Western storyline — chaos, irrationality, and collapse — says more about political agendas than about history.

The struggle over development

Since Mao’s death, critics have charged that the Cultural Revolution blocked modernization, targeted the Four Modernizations, or pushed “reactionary egalitarianism.” These charges fall apart the moment they’re examined.

The Cultural Revolution leadership never rejected technological development or improvements in people’s material lives. They rejected only the claim that modernization required reproducing capitalist hierarchies and sharpening economic divisions. They insisted that developing productive forces and narrowing class differences were not incompatible but essential to socialism.

Remember Marx’s “Critique of the Gotha Program.” Marx explained that socialism doesn’t start on a clean slate. It begins with “birthmarks” of the old society still attached. In the early stages, people receive according to the work they perform, not according to their needs. That system carries over some economic divisions from the past. Only through long-term development can a society reach the higher principle of “from each according to ability, to each according to need.”

The Cultural Revolution didn’t reject development — it rejected locking early, unequal arrangements in place. For Marx, “distribution according to work” was never a timeless rule; it was a stopgap shaped by the economic divisions inherited from capitalism.

Lenin later put it plainly: a workers’ state has to uphold certain inherited forms — wage norms, administrative routines, even legal coercion — even as it struggles to move beyond them. These contradictions don’t disappear; they create space for new privileged layers to form inside the socialist system.

The Cultural Revolution raised the question: how can a socialist society reduce economic divisions without undermining its own material base? Its answer was to mobilize the masses against privilege — not against productive labor. The struggle was aimed at those who defended hierarchy and special privileges, not at skilled workers or necessary specialists. When Soviet workers later protested managerial privilege, they faced similar accusations of “leveling.” In both China and the USSR, attacks on “levelers” were often veiled attacks on workers resisting bureaucratic domination.

The upheavals of the Cultural Revolution reflected how hard it is to wage class struggle inside a socialist state. Bureaucratic power had deep historical roots. The working class was still young, dispersed, and unevenly developed. China was under military and political siege — from its western borderlands to the Taiwan Strait. A revolution in these conditions won’t advance through polite argument. It has to fight — often fiercely — to hold its course and prevent new privileged layers from consolidating.

The defeat of the left after Mao

Mao’s death on September 9, 1976, opened a sudden struggle over where the revolution would go next. The arrest of Chiang Ching, Chang Chun-chiao, Wang Hung-wen, and Yao Wen-yuan weeks later signaled the defeat of the forces that had tried to keep class struggle at the center of socialist development.

The Shanghai working class — the backbone of the Cultural Revolution — did not mobilize in their defense. Whether workers were exhausted, confused, or simply outmaneuvered, the absence of resistance allowed the new leadership to move quickly and consolidate control.

What followed was a classic Thermidor — a term drawn from the French Revolution meaning a retreat from the revolutionary high point. It wasn’t a counterrevolution, but a sharp shift in power away from the revolutionary left and toward forces more willing to revive bourgeois norms and market pressures.

Recognizing this defeat is essential. The so-called “Gang of Four” were not a fringe group; they represented the current inside the Party that sought to defend — and deepen — the gains of the Cultural Revolution: workers’ oversight of officials, political struggle against bureaucratic privilege, and efforts to keep socialist planning under popular control. Their removal cleared the way for a right-center bloc that viewed these mechanisms of working-class supervision as obstacles rather than safeguards.

This setback had international repercussions. It strengthened conservative trends in the world movement and reinforced revisionist currents in the USSR and beyond.

Those who call the Cultural Revolution an “error” or “tragedy” misunderstand its purpose. It was a political and ideological battle waged under the most difficult conditions to defend the proletarian character of the revolution. It confronted the central contradiction of the socialist transition: socialist property relations can coexist with bourgeois social relations for an extended period, and unless the masses intervene, the latter can grow strong enough to turn the entire society backward.

The contradiction persists. Every socialist state is threatened not only by imperialist attack but by internal forces shaped by hierarchy, uneven economic conditions, and the persistence of commodity relations.

Imperialism has never let up. The same powers that once invaded and partitioned China, backed reactionary forces against the revolution, threatened nuclear attack in the 1950s, kept China out of the United Nations for a quarter-century, and ringed the country with military bases now work to weaken and contain its development. Whoever leads the Chinese state, Washington’s goal remains the same: to reduce China to a neocolonial subordinate.

Part 2: What a socialist state Is — and how it can be lost

A state marked by the old society

Lenin had a striking way of describing the first steps of socialism. He called the workers’ state, in a certain sense, “a bourgeois state without the bourgeoisie.”

What Lenin meant was straightforward. When workers take power, they don’t start from scratch. They inherit the machinery of the old society — wage systems, office routines, legal rules, managers and specialists shaped by capitalism. You can’t sweep all of this away overnight without stopping the economy. Some of these old forms have to remain for a time, even though they come from a society the revolution is trying to move beyond.

Lenin wasn’t saying socialism remained capitalism. He was pointing out that some structures carried over from capitalism had to be used for a time while new socialist relations were built through planning and the active involvement of the masses.

The early Soviet Republic made this contradiction plain. The Bolsheviks overthrew the old ruling class, expropriated the capitalists, and nationalized the banks and major industries. But they inherited a country shattered by war, with little industry and a largely illiterate population. To keep the railroads moving and the factories and hospitals running, they brought in thousands of former Tsarist specialists. These experts carried hierarchy and privilege with them into the new society. Lenin despised these traits, but he knew they couldn’t be swept away overnight. He called them the “birthmarks” of the old order — problems to handle while a new society was being built.

Lenin pointed out in “The Impending Catastrophe and How to Combat It” that monopoly capitalism had already built some of the structures socialism could use. The big capitalist trusts had centralized production on a huge scale. Under a workers’ state, that machinery could be turned toward planning. The form looked capitalist, but its purpose changed once it came under proletarian control.

The same was true of surplus value. Workers still perform surplus labor under socialism — but it’s no longer taken as private profit. The issue is who controls that surplus and what it’s used for. In the early USSR, it went into the state budget and was used to expand production, build schools and hospitals, and defend the new society.

But the Soviet experience also showed the dangers. A privileged bureaucratic layer can grow even without a capitalist class. Some officials began to claim better conditions and use their positions to steer resources toward themselves. Lenin warned again and again that if this wasn’t checked, it could bring back the very inequalities socialism set out to end — and even open a path back toward capitalism.

The crisis that led to the New Economic Policy brought these contradictions into the open. Civil war had wrecked the economy, hunger was spreading, and peasant uprisings threatened the workers’ state. War Communism — an emergency system of tight central control — had hit its limit. Lenin introduced the NEP as a tactical retreat: a temporary use of markets, small private trade, and limited foreign concessions so the revolution could survive.

Even then, the core of the economy stayed under workers’ control. Heavy industry, banking, and foreign trade remained in state hands. The “NEPmen” ran small shops and petty businesses, but they had no political power. The whole setup was understood as temporary — a breathing space. By the late 1920s, the NEP gave way to socialist industrialization. Its contradictions were real, but they didn’t produce a capitalist class.

Lenin’s approach helps in understanding China today. A workers’ state in a capitalist world can’t build socialism with brand-new tools; it has to work with what it inherits — markets, private firms, even foreign investment — while holding political power in working-class hands. These compromises don’t mean capital runs China. They show the contradiction China is working through: capitalist pressures on one side, and a Party and state that still direct planning, mobilization, and national development on the other.

What matters is not whether capitalist methods appear, but whether capitalist relations take command.The party and the state: two different tasks

Lenin made a distinction that matters for any socialist transition, including China’s. The workers’ state and the revolutionary party don’t play the same role. When those roles blur, the risks of bureaucracy, privilege, and even pressures toward reversal grow quickly.

The state takes on the practical work of running a modern society. It has to keep production going, defend the country, manage distribution, and keep daily life functioning. That can’t be done by willpower alone. It depends on inherited forms — wage systems, managerial layers, legal structures, accounting methods, and specialists shaped by the old society.

The party, though, has a different role. Its task isn’t to operate the old machinery the revolution inherited, but to move society beyond it.

Under socialist construction, the party’s role is to help the working class make sense of the society it is building. By drawing on people’s own struggles and experiences and working through them collectively, the party strengthens the political understanding needed to guide production, defend the revolution, and solve problems together. This helps millions take part in running the country and shaping its direction — not as spectators, but as active participants.

The party has to push back against the pull of old habits — privilege, hierarchy, and the notion that some people deserve more because of their position or skill. These are remnants of “bourgeois right,” the old idea that unequal rewards are normal. The party’s work is to keep the masses at the center of socialist construction and hold to the aim of a society without exploitation or deep-rooted economic divides. It is the conscious force that moves beyond the limits the state still has to manage.

Lenin warned that without this distinction, the party could be pulled into the state apparatus. When party cadres start to see themselves mainly as administrators — managers, supervisors, technical overseers — the inherited forms of capitalism can stop being temporary tools and start rebuilding capitalist relations. Specialists, managers, and bureaucrats, necessary in the early period, can consolidate privileges that widen the distance between the apparatus and the working class. The result isn’t just inefficiency or corruption, but social forces whose interests point back toward bourgeois norms.

A socialist state operating in a hostile capitalist world may allow private enterprise, rely on market signals, use wage differentials, or enter joint ventures with foreign companies. These measures don’t by themselves determine the system’s class character. What matters is who directs them and for what purpose. Under a capitalist state, “state capitalism” strengthens bourgeois rule. Under a socialist state, similar measures can be used to develop socialist property, defend national sovereignty, and build the foundations of a new society.

But this is possible only if the party holds on to its revolutionary character — if it continues to act as an organizer of class struggle rather than slipping into the role of an administrative appendage. When the party sinks into the state and lets its transformative work fade, the advantages held by officials and specialists can harden into a new hierarchy that threatens the gains of the revolution.

This danger is not abstract. It shaped the internal crises of the Soviet Union and later China. In both cases, when the party slipped into bureaucratic administration or adopted a pragmatism cut off from class analysis, privilege grew, inequalities widened, and the pull of the capitalist world market strengthened. The contradictions of socialist transition — the birthmarks of the old world — became openings for pressures toward restoration.

For China, the point is straightforward. A socialist state may use markets, allow private capital, or take part in global trade as part of its development. But the party cannot turn these practical steps into permanent principles. Its task is to push back against capitalist pressures, keep concessions from hardening into new class interests, and hold the transition on a socialist path.

This distinction between party and state — between administration and transformation — shaped the crises of both the Soviet Union and China. In the USSR, the Communist Party’s slow absorption into the state weakened its ability to push back against the bureaucratic forces that later lined up with restoration. In China, the Cultural Revolution grew out of the sense that too many officials were becoming administrators cut off from revolutionary aims. And when Deng Xiaoping expanded market mechanisms, the danger was not only economic but political: the Party could stop trying to change capitalist relations and instead end up managing them. To see how these tensions played out — in the Soviet experience, in Mao’s time, and in the decades since — we have to look closely at their actual history.

The consequences of misidentifying class forces

The Sino-Soviet rift grew out of U.S. imperialist maneuvering and the shift in the Soviet leadership after Stalin. But inside that conflict, some of the Chinese leadership’s own formulations carried their own contradictions. In the heat of the struggle, Mao called the Soviet bureaucracy a “new bourgeoisie,” a phrase that blurred the difference between bureaucratic privilege inside a workers’ state and an actual capitalist class.

The Soviet Union had real bureaucratic distortions — Lenin once wrote, “What we actually have is a workers’ state … with bureaucratic distortions” — but it remained a workers’ state until its final years. The bureaucracy was a corrosive layer, not a new owning class with its own property system.

When the USSR was described as “social imperialist,” the distinction between a workers’ state weighed down by bureaucracy and a capitalist-imperialist power was lost. Once that line was blurred, the basis for proletarian internationalism weakened. If the Soviet Union was treated as a capitalist empire — no different from or even worse than the U.S. — then the whole map of friends and enemies shifted.

Once the USSR was cast as the main danger, tactical cooperation with the United States became thinkable. The irony is clear. The Cultural Revolution, launched to challenge what Mao saw as a drift toward capitalist practices, also created openings that U.S. imperialism later used. The approach to Washington begun under Mao to counter the USSR became, under Deng, one of the routes through which market mechanisms and deeper integration into global capitalism advanced.

The weakening of planning’s ideological foundation

A similar pattern appeared in the attacks on planning. The Cultural Revolution aimed to confront bureaucratic privilege — the layer of officials drifting away from the working class. But as the struggle sharpened, the planning apparatus itself was sometimes cast as the problem, as if the tools needed for socialist development were simply another expression of entrenched bureaucratic power.

This blurred the distinction between bureaucracy and planning. Planning, with all its flaws and risks of abuse, stopped being viewed as a means for working-class control and started to look like a source of domination. In criticizing the “Soviet model,” the fight against bureaucracy ended up weakening institutions that socialist development depended on.

By the late 1970s, supporting planning could be branded as “pro-Soviet” or “revisionist.” Left forces inside the Party found themselves on the defensive, unable to offer a clear alternative to market policies without being tied to a model that had fallen out of favor during the Cultural Revolution’s last years. This opened space for the new leadership to argue that expanding market mechanisms was not a turn toward capitalism but a necessary correction to bureaucracy.

The theoretical vacuum and its exploitation

These shifts left an ideological gap. If the Soviet Union was no longer seen as socialist, and if planning itself was treated with suspicion, the meaning of socialism drifted toward something abstract — a moral stance rather than a concrete system of property, planning, and working-class power.

This gap also dulled the Party’s sense of how class forces develop. Without a clear understanding of how capitalist relations reappear inside a socialist state, the rise of private capital, wage gaps, and market competition could be treated as neutral measures instead of signs of class pressures. A new privileged layer could grow without being named, because the tools for identifying it had been blunted.

The Three Worlds Theory pushed this further. It cast the U.S. and the USSR as competing “superpowers” and grouped China with the “Third World,” a framing that stripped the global struggle of its class content and turned it into a rivalry among states. By treating the Soviet Union as the main danger, national strategy rose above proletarian internationalism, and cooperation with Western capital began to appear normal.

Deng kept this strategic outlook while putting aside the older language. Special Economic Zones, joint ventures, and foreign investment became the economic expression of a geopolitical direction already taking shape.

This doesn’t mean the Cultural Revolution paved the way for Deng — the two tracks were opposed. But some of the conclusions reached in its final years — calling a privileged layer a “new bourgeoisie,” weakening support for planning, and treating the USSR as a “superpower” rather than a workers’ state — created openings that later leaders could use.

These unresolved tensions set the stage for the battles that followed Mao’s death.

The exhaustion that opened the door

By 1976, the Party had endured ten years of fierce struggle. The Cultural Revolution energized the masses but also left institutions strained and divided. Many provincial and local cadres wanted stability and clear administration, not a retreat from socialism. Deng tapped into this desire. His message of “emancipating the mind,” restoring order, and focusing on development appealed to those who associated mass mobilization with disruption instead of strength.

Mainstream narratives portray Deng Xiaoping’s ascent as “pragmatism” triumphing over ideology, with “seeking truth from facts” held up as proof that socialism needed the market to move forward. But this framing masks the substance of the turn: a rebalancing away from socialist planning and toward market mechanisms that widened the space for capitalist relations and a new layer of privilege.

In practice, Deng’s “pragmatism” meant loosening central controls, shifting authority to local governments, inviting foreign capital, and restoring profit incentives in agriculture and industry. None of this was presented as a break with socialism. Deng argued it was necessary to “develop the productive forces,” even if it meant “letting some people get rich first.” “Socialism with Chinese characteristics” became the ideological cover for a strategy whose real content was the broad expansion of market relations inside a socialist state.

Lenin warned that philosophical “pragmatism” — judging policies only by what seems to work in the moment — is a bourgeois outlook. Capitalism encourages people to prize whatever “works” inside the system rather than question the system itself. When this becomes the guiding method, it can end up restoring what socialism seeks to move beyond. In China, policy debates increasingly turned not on socialist principle but on which measures brought in investment, raised output, or filled local budgets.

A large private sector was developed. State enterprises were restructured, corporatized, or privatized. Stock markets were created. Foreign capital flowed into Special Economic Zones. Profit became the central regulator of vast sectors of the economy. A domestic bourgeois layer took shape — not dominant, but increasingly visible and even represented in official bodies like the National People’s Congress.

As market policies advanced, administrative authority became a key site of private enrichment. Officials who controlled land approvals, credit access, and restructuring decisions held practical gatekeeping power in a partially marketized economy. Property remained publicly owned, but access flowed through discretionary decisions and personal networks. This allowed a new layer of well-connected officials and intermediaries to turn political position into material advantage, even if they were not private owners of capital.

By the 1990s and 2000s, corruption was woven into the development model itself. Local governments relied on land leasing and real-estate projects to finance budgets, creating strong incentives for rent-seeking. Guanxi networks — webs of personal ties functioning much like U.S.-style political patronage or insider connections — adapted to the new environment, serving as channels for favoritism, insider access, and protected deals, while princeling families moved easily through banking, real estate, and emerging private industries. Periodic crackdowns hit prominent cases but left the structural incentives of market policies intact. Corruption was not a deviation from the system — it became one of its regular operating methods.

The spread of corruption reshaped everyday life as well. As land deals, real-estate projects, and insider networks became central to local growth, uneven economic conditions widened and regions diverged sharply. Speculation bled into housing, finance, and enterprise, creating bubbles and new avenues for abuse. For working people, the transition meant plant closures, layoffs, and growing insecurity. Poverty increased dramatically and income inequality is roughly in the same high range as the U.S.

At the same time, a narrow layer — those with special access to state authority and emerging market opportunities — was able to secure personal fortunes and privileges that had been impossible in the Maoist years. The social fabric tightened and frayed under these pressures, exposing divisions that earlier decades of socialist construction had struggled to contain.

Gramsci and China: War of position?

In some academic and left circles, a claim has taken hold that China’s post-1978 turn reflects Antonio Gramsci’s idea of a “war of position.” In this view, China’s entry into the world market was a strategic move — using the existing system to build national strength while keeping state power firmly in Party hands. Market policies are reinterpreted as a long, patient road toward socialism.

It’s an appealing argument: the notion that Deng’s direction was not a retreat but a slow advance.

And it’s true that the Party kept political control through these years. But that alone doesn’t make it a “war of position,” nor does it match what Gramsci was talking about.

Gramsci used “war of maneuver” and “war of position” to describe two ways revolutionary struggle can unfold: a direct fight for state power, or a slower effort to build working-class strength inside society itself.

His idea of a “war of position” grew from studying advanced capitalist countries, where the bourgeoisie ruled not only through force but through dense cultural, political, and ideological institutions. In that setting, it meant building up proletarian strength in civil society — creating workers’ institutions, cultural influence, and political authority capable of challenging bourgeois rule. The aim was to develop the working class as an independent force, preparing it for a future confrontation over state power.

A real “war of position,” then, is not defined by holding political power at the top. It depends on strengthening the organization, confidence, and institutions of the working class — expanding its role in economic life and deepening its place in society. Without that, the concept doesn’t hold.

What Deng’s policies actually did

Nothing in Deng’s approach resembled a “war of position.” The policies did not build independent working-class institutions — many that existed were weakened or dismantled. They did not broaden the role of the proletariat — they expanded market relations, profit incentives, wage gaps, and competition. They did not strengthen collective participation — they elevated managers and empowered local officials who increasingly acted like corporate executives. Whatever “positions” were gained belonged to administrative and market actors, not the working class.

Deng never presented it differently. He did not speak of building working-class leadership or preparing the ground for a higher stage of socialism. His focus was straightforward: growth, investment, productivity — even if this widened inequality and fostered private wealth. The language of class struggle faded, replaced by talk of efficiency, modernization, and national revival.

The use of Gramsci to explain this turn repeats an old pattern. After Gramsci’s death, Palmiro Togliatti and the Italian Communist Party recast the “war of position” as a rationale for settling into permanent parliamentary accommodation and postponing any break with the capitalist state.

What began as an analysis tied to specific conditions in Gramsci’s notebooks became, under Togliatti, a cover for class collaboration. (A sharp contemporary critique came from the Communist Party of China in the December 31, 1962 People’s Daily editorial “The Differences Between Comrade Togliatti and Us,” which challenged Togliatti’s parliamentary line and linked it to the wider revisionist drift of the Soviet leadership.)

In both cases, Gramsci’s categories — pulled out of their original context — end up serving as alibis for retreat.

This Gramsci-inspired reading also obscures the real contradiction. China is not carrying out a quiet, long-term socialist siege through capitalist methods. It is moving through a contested terrain where socialist forms coexist with expanding capitalist relations — and the struggle over which direction will prevail is still unresolved.

Lenin’s NEP and Deng’s turn: two different roads

Comparisons between China’s post-1978 policies and Lenin’s New Economic Policy are often made, but the situations were fundamentally different. Both used markets, but for different reasons and with different results.

Lenin introduced the NEP in 1921 to pull a workers’ state back from the edge of collapse. It was conceived as a temporary step. Heavy industry, banking, transport, and foreign trade stayed under workers’ control. Private traders operated at the margins and held no political power. After seven years, the NEP was replaced by socialist industrialization.

Deng’s course pointed in a new direction entirely. China in 1978 was not facing a breakdown of the state. Household contracts, rural markets, joint ventures, and other early measures were framed as a long-term approach. Over time, they created a mixed economy: a sizable private sector, corporatized state firms, stock markets, and expanding foreign capital. Profit became a central regulator, and a domestic capitalist stratum took shape.

The contrast is straightforward. Lenin allowed narrow private trade while keeping full command of the decisive sectors. Deng’s changes brought capitalist relations into a socialist framework. And while the NEP lasted seven years, China’s market era has continued for more than 45 years — long enough to alter class relations and form new social forces.

Even so, China did not undergo full capitalist restoration. The state still commands the strategic sectors, the financial system, the military, and the overall direction of national development. Planning capacity remains. These pillars keep China in a contradictory position: a workers’ state in structure that coexists with expanding capitalist pressures.

This is why the NEP comparison doesn’t hold. Lenin made a tactical retreat; Deng embarked on a structural shift.

And the end of the NEP did not settle the question of direction in the Soviet Union. As the USSR moved forward, new contradictions emerged inside the workers’ state itself — contradictions that shaped its whole trajectory.

The contradictions that developed

From its earliest years, the Soviet Union faced pressures that ran through the whole system. These didn’t come from “central planning” or “state ownership,” as Western accounts often claim, but from building socialism while surrounded by hostile imperialist powers, pushed into rapid industrialization, and dependent on specialists trained under Tsarism.

Over time, these layers developed into a privileged stratum. They were not a bourgeois class in the Marxist sense — the major industries, banks, and land were no longer privately owned, and state power rested with the working class. But this stratum increasingly tried to secure its position by narrowing mass participation and weakening mechanisms of workers’ oversight. Imperialist pressure only sharpened these tendencies.

As the USSR poured resources into defense and scientific competition, the administrative layers grew more cautious. Their distance from the working class widened as the country shifted from revolutionary mobilization to defensive consolidation.

By the 1970s, these pressures had produced an atmosphere in which parts of the administrative and managerial layers began looking to the West not simply as an opponent, but as a model for economic change and personal advancement. The contradictions of a socialist state under siege had produced a layer whose outlook aligned with the push toward capitalist restoration.

Why the Soviet Union collapsed

The fall of the Soviet Union is often cited as proof that socialism can’t work or that planning is bound to fail. But the collapse was political. The socialist state broke apart when part of its own administrative elite abandoned socialist property relations and embraced capitalist restoration. The decisive break wasn’t economic stagnation alone; it was the transfer of state power to forces committed to dismantling the socialist foundations of the system.

The turning point came in the 1980s, when Gorbachev’s policies — framed as “modernization” — opened space for this stratum to assert itself. Central planning was weakened, Party authority loosened, and bourgeois ideology reentered political life. Anti-socialist intellectuals, Great Russian chauvinists, and pro-market factions gained ground. The Party split, and the state began to come apart.

Under the banner of Perestroika, the USSR moved from full state ownership and centralized planning toward a mixed setup: private cooperatives, semi-autonomous state enterprises, and market pricing for key goods. These changes undercut the socialist core of the economy and opened the way for profit-driven practices.

At the same time, Great Russian chauvinism — which Lenin had warned against from the outset — resurfaced as an organizing force under Gorbachev. Moscow’s dealings with the non-Russian republics, especially in Central Asia and the Caucasus, took on a tone of condescension and control. Accusations of “corruption” or “backwardness” ran downward from a Russian-dominated leadership toward formerly oppressed peoples, turning what should have been comradely relations into something else entirely.

Institutional changes reinforced this shift. In 1989 Gorbachev reduced the authority of the Soviet of Nationalities, and in 1991 he abolished it outright — just months before the dissolution of the USSR. That chamber had given every republic its own delegates and an equal voice in decisions affecting the whole union. Dismantling it marked a break with proletarian internationalism and reasserted Russian dominance, deepening the fractures that tore the union apart.

Not long after, the pro-capitalist wing inside the state moved decisively. They dissolved the USSR, privatized state assets, and turned themselves into a new capitalist class. The 1991 collapse was not an inevitability or an act of nature. It was the outcome of a political fight in which the pro-capitalist forces within the bureaucracy won. Restoration was not an accident. It was a bourgeois class victory.

Why Deng was not China’s Khrushchev

This raises an obvious question: Is China following the same path? Some on the left draw an analogy between Deng Xiaoping and Nikita Khrushchev. Both emerged after periods of upheaval; both criticized parts of the previous leadership; both promised “modernization.” But under Marxist analysis, the comparison falls apart. The political content of their courses diverged sharply, and equating them obscures the class dynamics of both experiences.

Khrushchev represented a real degeneration at the top of a socialist state. His “secret speech” undercut the ideological foundations of Soviet socialism, weakened Party authority, and opened space for anti-socialist forces at home and abroad. His policies encouraged conciliation with imperialism, weakened planning, and strengthened administrative layers whose interests drifted away from the working class. The USSR remained a socialist state, but Khrushchev accelerated the contradictions that helped bring about its eventual collapse.

Deng Xiaoping’s course was different in character. He did not repudiate the revolution or revive bourgeois politics. He did not dismantle the Communist Party or the state sector. He did not abandon the dictatorship of the proletariat, even though the term slipped out of use. The Party retained its political monopoly, control of the military, and command over the strategic core of the economy. Deng did not build a bourgeois state; he reorganized a socialist state.

The danger in Deng’s policies came not from political liberalization but from the expansion of capitalist relations inside a socialist framework. Market mechanisms expanded, private capital grew, and a new privileged stratum took shape around foreign investment, export industries, and domestic accumulation. These forces pushed toward capitalist restoration, but they did not achieve it. The state remains the dominant economic actor, planning continues in key sectors, and the Party’s supremacy is not in question.

The forms differed; the dangers differed; and so did the outcomes. Deng did not frame restoration as his political goal; he aimed at rapid development, but the methods he relied on strengthened forces capable of pushing in that direction. Yet unlike the Soviet bureaucracy — which by the late 1980s acted increasingly as a force aligned with capitalist restoration — the Chinese Communist Party maintained firm control over the state apparatus, the military, the banking system, and the commanding sectors of the economy. Party leadership did not erode; it consolidated.

This is the decisive distinction. Restoration is not the presence of capitalist relations — it is the victory of a capitalist class over the political framework of a socialist state. That occurred in the USSR, shaped in part by Khrushchev’s course and completed under Gorbachev and Yeltsin. It has not occurred in China because the Communist Party retained control over the state and continued to direct national development. How to avoid the Soviet outcome has become a central preoccupation of China’s leadership.

Xi Jinping and the reassertion of political control

By the time Xi Jinping took the helm, China had already experienced more than thirty years of expanding market relations. The growth of that period rested not on the market itself, but on the socialist foundations built in the Mao era — the public ownership, planning capacity, and industrial base that made large-scale development possible.

Those decades of market expansion also produced forces that pressed against the socialist character of the state. A patchwork of local power blocs had formed. Officials built personal networks through land deals, credit channels, and business ties. Private capital gained significant weight, especially in finance, real estate, technology, and export production.

In many areas, Party committees acted less as organs of proletarian rule and more as brokers among competing capital-centered interests. The Party center’s ability to set and carry out national priorities was weakened.

This still wasn’t capitalist restoration; the main sectors of the economy remained publicly owned and under Party direction. But it did create a political climate where private wealth and bureaucratic privilege became increasingly intertwined.

A privileged layer becomes a political danger

The blending of political authority with private wealth produced a privileged layer whose interests leaned toward expanding the market. They were not capitalists in the classical sense — they did not own China’s major industries or banks — but they occupied positions where access to resources, licenses, land, and investment could be turned into personal gain. Their privileges grew out of the coexistence of socialist ownership and an expanding market.

This layer did not yet have the cohesion or independence of a capitalist class, but it was becoming a force that could weaken the socialist state. Local governments relied heavily on land and real-estate deals to fund their budgets, and officials tied to developers pushed projects that enriched a few while raising costs for millions. In the military, some officers oversaw sprawling business operations; in state firms, executives acted as if they were private owners. Taken together, these trends pointed toward a long-term risk: the gradual formation of a political bloc capable of challenging Party leadership.

The Communist Party’s own assessments repeatedly cited the Soviet collapse as a warning. In their view, the USSR fell because its Party no longer functioned as a unified political force. Factionalism, ideological drift, and an entrenched layer of privilege opened the way for restoration. China’s leadership concluded that similar dangers existed within their own system — and that they had to be addressed before they hardened into a decisive break.

The anti-corruption campaign as political struggle

The anti-corruption campaign launched in 2013 was the clearest sign of a counteroffensive by the Party. Western commentary framed it as a purge or a power grab, but its focus was the entrenched interests that had grown under decentralization: military officers running business empires, provincial leaders with patronage machines, SOE (state owned enterprise) executives acting like private owners, and cadres maintaining parallel structures outside central oversight. Within a few years, millions of officials had been disciplined, senior military figures removed, and major state enterprises shaken. The aim was not moral reform; it was to break apart a political order in which capital, privilege, and local networks were cutting into the authority of the socialist state.

The Party often pointed to the Soviet collapse in explaining its approach. In its reading, the USSR fell when the Communist Party stopped functioning as a unified political force. Factionalism, ideological drift, and a privileged layer aligned with restoration opened the way for anti-socialist forces to seize the state. China’s leadership concluded that if the Party lost discipline, coherence, or control over the military and key institutions, a similar outcome was possible.

This shaped the anti-corruption drive: a defensive struggle inside the socialist state. Its purpose was to stop fragmented authority from hardening into a political force that could challenge central leadership. In effect, it was class struggle carried out through Party discipline rather than mass mobilization — an effort to restore unity in a system pulled toward localism and private power.

Xi’s turn went beyond discipline. It aimed to redirect the course of development. For years, local governments had chased GDP growth through real-estate bubbles, debt-driven construction, and speculative projects that sidelined social needs. Xi’s “new development concept,” the poverty-alleviation push, and moves against tech monopolies and shadow finance were attempts to shift development away from speculation and toward steadier, strategically guided growth.

The poverty-alleviation campaign underscored this shift. It redirected state priorities and required officials to deliver tangible improvements in people’s lives rather than relying on inflated growth numbers. It marked a reassertion of planning capacity in a system where market forces had steadily crowded out planning.

There was also an ideological turn. Renewed emphasis on Marxist education, Party discipline, and the subordination of private capital to national priorities signaled an effort to rebuild an ideological grounding that had thinned through years of pragmatism. The aim was to block the rise of a bourgeois political force inside the Party.

None of this reversed the expansion of capitalist relations. The private sector remains large, market pressures shape much of daily life, and the incentives behind corruption still exist. Local governments continue to rely on land-use leases and development deals to finance their budgets, and profit continues to act as a major regulator in wide areas of the economy. The “power–money nexus” has been shaken, but not dismantled.

What Xi’s leadership has done is contain — not resolve — the contradictions created by four decades of market policies. It shows that the Party can restrain capital and reassert collective priorities, but it also reveals how deeply capitalist pressures run through the system. The struggle between socialist foundations and expanding capitalist forces remains open.

The poverty-alleviation campaign as a socialist mobilization

China entered the period when Deng’s market policies were introduced with one of the lowest extreme-poverty rates in the developing world. The socialist institutions built in the Mao era had already raised living standards and secured basic needs for most people. From 1981 to 1990 — the last decade shaped by those institutions — extreme poverty averaged about 5.6%, far below India, Indonesia, or Brazil.

During the market turn of the 1990s, however, extreme poverty surged. Price deregulation drove up the cost of food and housing, wages lagged, and the purchasing power of low-income households collapsed. At the height of this transition, roughly 68% of the population fell below the extreme-poverty line — a sharp reversal of the gains made in the Maoist period.

When China announced the eradication of extreme poverty in 2020, Western commentary treated it as an administrative accomplishment. But the campaign had a different character. It marked the reassertion of collective priorities by a socialist state in a system long steered by market forces. It showed that broad mobilization for social needs was still possible within a contradictory, marketized structure.

Xi Jinping’s targeted campaign went directly at the problem rather than waiting for market growth to lift incomes. The state used its administrative and financial power to ensure that every household met basic material standards — food, clothing, compulsory education, essential healthcare, and stable housing. This minimum social floor was something the market had never provided.

The approach drew on China’s revolutionary traditions. Millions of cadres were sent to rural areas to assess each household’s needs. Families received income support, new housing, relocation when required, and access to schools and clinics. Roads, power grids, water systems, and communications were built or upgraded — projects the market had ignored as unprofitable.

The central government redirected large resources to the poorest areas and changed the incentive system that had long rewarded GDP-driven development. Cadres were evaluated by concrete improvements in people’s lives rather than investment numbers or real-estate output. Collective needs were placed above market priorities.

Market institutions were also pulled into the effort. State banks offered subsidized credit. Large private firms were pressed through Party channels to take part in support programs. Universities, state enterprises, and provincial governments were paired with poor regions in a nationwide assistance system. The campaign did not undo marketization, but it showed that the socialist state could direct the market rather than simply adjust to it.

International institutions recognized the scale of the achievement but often missed its core meaning: this was not a triumph of markets, but of planning capacity and Party leadership. In a system marked by uneven development and expanding private capital, the campaign showed that collective authority still had weight.

Part 3: Why China shakes the imperialist order

China is not imperialist

The claim that China has become an imperialist power is now routine in Washington, the corporate press, and parts of the left influenced by liberal geopolitics. It is repeated so often that it passes for truth. But it collapses under Marxist analysis. Imperialism, as Lenin defined it, is not simply “big-power behavior.” It is a stage of capitalism in which monopoly finance capital dominates, exports capital to oppressed nations, and extracts super-profits through the ownership and control of entire regions and economies.

Judged by this standard, China is not an imperialist power. Its economy is large and its global presence growing, but its actual role bears no resemblance to the historic imperialist centers that built the modern world capitalist system.

Imperialism rests on finance. Its core instruments are global banks, reserve currencies, structural adjustment programs, debt peonage, and the power to reorganize entire economies. This system — built by the U.S., Britain, Germany, France, and Japan — is anchored in the IMF, the World Bank, dollar dominance, and multinational corporations backed by military blocs.

China does not command such a system. Its currency is not a world money. Its banks do not dictate policy to other nations. It does not enforce austerity packages, impose privatization, or conduct economic warfare through sanctions.

When China lends to developing countries, the terms often reflect hard bargaining, uneven benefits, and occasionally dependency — but they do not replicate the debt-peonage system through which Western finance capital governs the periphery. Chinese loans are routinely renegotiated, extended, or forgiven; they do not function as levers to impose privatization, deregulation, and austerity programs on borrowing countries.

China does not extract monopoly super-profits through control of global finance or intellectual property. In reality, it was Western corporations that extracted vast value from China for decades. China’s industrial ascent has altered its role in production, but the commanding heights of global finance remain centered in New York, London, Frankfurt, Paris, and Tokyo.

Military position makes the difference even clearer. Imperialism rests on armed coercion: bases, alliances, interventions, and the global command structure that enforces the capitalist order. The United States maintains roughly 750-800 foreign bases; China has one. The U.S. operates worldwide combatant commands; China does not.

China’s foreign policy emphasizes sovereignty largely because it spent a century as a target of colonial domination, not a beneficiary of it.

China is not a new imperialist center — it is a still-developing country rising in a world order built by others. Its income levels remain far below those of the U.S. and Europe, and many areas still depend on state-led development. The jobs China must do — raising living standards, lifting up poorer regions, and building its own industries — were handled in the rise of the imperialist powers through centuries of colonial plunder. China is doing it without that stolen wealth.

This does not mean China operates abroad as a socialist alternative. Its external activity is shaped by national priorities and the mixed character of its economy. Chinese companies invest overseas to make a profit, sometimes with state backing, and some projects have uneven effects. But this still does not place China in the category of an imperialist power. It is better understood as a post-colonial industrializing country working within a global order long dominated by the imperialist capitalist powers.

China’s foreign policy shift

China’s foreign policy has shifted over time. For decades after 1949, its approach reflected the conditions of a nation emerging from colonial subjugation and civil war. China did not possess overseas corporations or global banks. What it had were political commitments shaped by its own experience of imperialist domination.

In its early decades, China’s foreign policy was explicitly revolutionary. The Communist Party viewed national liberation movements as part of a shared world struggle against colonialism and capitalism. Beijing actively supported communist and anti-imperialist movements across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, providing material aid, training, and political backing to liberation struggles and insurgencies.

This was not symbolic solidarity. China supplied Korea and Vietnam in their wars against U.S. intervention; sent medical teams, engineers, and military advisers to movements in Algeria, Guinea-Bissau, Angola, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe; and completed the Tanzania–Zambia Railway in 1975 to help newly independent states break free from apartheid-controlled trade routes.

China viewed these efforts as extensions of its own struggle against foreign domination and as support for newly independent states up against the same imperialist system.

This outlook also shaped China’s participation in the Bandung Conference in 1955, which brought together 29 newly independent Asian and African nations, a significant show of anti-imperialist unity among formerly colonized peoples.

China’s foreign policy aligned with the wave of anti-colonial revolutions then sweeping Asia, Africa, and Latin America as nations fought to end imperialist domination.

The Sino-Soviet split disrupted this unity. Differences over strategy, ideology, and how to confront U.S. power hardened into a rupture that divided the socialist camp. During the Cultural Revolution, the Soviet Union was portrayed inside China as a warning of what happens when a workers’ state retreats from revolutionary struggle. But despite its bureaucratic contradictions, the USSR was not an imperialist power, and the deepening antagonism between Beijing and Moscow weakened the combined strength of states and movements resisting U.S. imperialism.

The consequences were visible by the 1970s. As the Sino-Soviet conflict intensified, China moved toward a tactical accommodation with Washington. Nixon’s 1972 trip to Beijing represented a real political shift. In southern Africa and Southeast Asia, liberation movements found themselves navigating conflicting positions from Beijing and Moscow. The coherence of the anti-imperialist front eroded at a moment when U.S. power remained formidable and on the offensive.

After Mao’s death, China’s leadership undertook a major reorientation. Deng Xiaoping argued that the country’s survival required concentrating resources on economic development.

Revolutionary assistance abroad was ended. China sought technology, loans, and investment from the advanced capitalist countries, normalized relations with the West, and entered the world market.

Its foreign policy language shifted accordingly, stressing stability, sovereignty, and the need to operate within a world system still dominated by the imperialist powers led by the United States, alongside Britain, Germany, France, and Japan.

These adjustments reflected the pressures facing any society attempting independent development within a global capitalist order. They did not transform China into an imperialist power, nor did they produce a socialist alternative for other nations. They marked a shift in priorities under difficult conditions — a retreat from earlier international commitments in order to secure national development in an environment shaped by Western finance capital and the military might of the United States.

China’s path — from supporting liberation movements to navigating a hostile world economy — shows the enormous pressures placed on any post-colonial society seeking to develop without plunder or overseas domination. These changes did not turn China into an imperialist power, but they did narrow the space for the kind of revolutionary commitments it once pursued. What followed was shaped by this contradiction: a country that is not imperialist, yet operating inside a world system made by the imperialist powers.

The Global South and the Belt and Road Initiative

China’s expanding role in the Global South is often held up as proof that it has become a new imperialist power. But the reality on the ground tells a different story. Belt and Road — the centerpiece of China’s overseas development activity — does not operate like the IMF, the World Bank, or the great colonial powers whose investments were designed to extract wealth and enforce dependency.

For decades, countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America faced only one model: loans tied to austerity, privatization, and foreign control. China’s approach breaks from that pattern. It finances ports, rail lines, power plants, and industrial zones without demanding that governments sell off public assets or dismantle social programs. When debts become difficult, Beijing typically restructures them, extends maturities, or forgives portions outright. China pursues its own interests, but it does not use debt the way imperialist powers do — as a weapon to force austerity, privatization, or political control.

None of this means China is charitable. Chinese firms seek profit, and China gains strategic influence. But the relationship is not one of domination. Belt and Road projects usually involve infrastructure-for-trade or infrastructure-for-resources arrangements — not the debt-for-privatization model used by Western finance capital. In many countries, these projects are the first major public works built in generations, expanding local capacity rather than hollowing it out.

China’s position as a nation once carved up by foreign powers also shapes its outlook. Its foreign policy stresses sovereignty and non-interference because it still carries the memory of colonial subjugation. Whatever contradictions exist within its system, China does not behave like the imperialist states that rule the world through force, finance, and unequal treaties.

This alternative — a major industrial country offering development without political control — has opened space for the Global South to maneuver in ways that were impossible under U.S. and European domination. It is one of the key reasons “multipolarity” has become such a common theme in international politics today.

Multipolarity: a description, not a destination

“Multipolarity” has become a dominant theme in international discourse. Governments in Asia, Africa, and Latin America speak of a world with several major power centers, and China and Russia present it as an alternative to U.S. dominance. Some voices on the left cast it as a step forward, and for people challenging U.S. imperialism, can seem like a hopeful counterweight.

But multipolarity describes relations among states, not social systems. It says nothing about exploitation, ownership, or class power. A multipolar world is still a capitalist world — still an imperialist world. It only indicates that U.S. supremacy is being contested, not that it has been overturned or that the global order has changed in any fundamental way.

For the Global South, the idea that multipolarity creates broad new room to maneuver is often overstated. A more contested world system can offer alternative partners and limited leverage, but the core structures of imperialist power remain in place. Whatever space appears is narrow, unstable, and easily closed. It is not a path to development, nor a substitute for anti-imperialist or socialist struggle.

Marxists begin from class, not geopolitics. Knowing that the world is “multipolar” tells us nothing about who owns the banks, who controls production, or who appropriates the surplus. A world with multiple power centers can still be a world ruled by capital; multipolarity does not resolve the basic contradiction between socialized labor and private appropriation.

China’s position in this landscape is shaped by its own internal contradictions and by the pressures of the existing imperialist system. Whether a more contested world order alters those pressures in any meaningful way is uncertain and uneven, and there is little historical basis to assume it will. What is clear is this: China does not promote multipolarity as a socialist project, but as a national strategy within a capitalist world system. This reflects its dual character — a socialist state with significant capitalist sectors navigating an international order still dominated by the old imperialist powers.

Multipolarity is not an alternative to socialist internationalism. It is not a program for liberation. Treating it as such repeats earlier errors, when alliances with “progressive” capitalist states were mistaken for class struggle. Multipolarity offers a description of shifting state relations, not a path beyond capitalism. The central struggle remains the same: the fight of workers and oppressed peoples against the global imperialist system of exploitation.

When the super-profits run out

What alarms Washington is not the talk of “multipolarity” or the emergence of other powerful centers on the world stage. The real threat is material: as China builds up advanced industry, it closes off the sectors where imperialist monopolies make their biggest profits. That strikes at the economic base of U.S. dominance far more than any shift in alliances or changes in official rhetoric.