There is a figure in Cuba’s history who was crucial to Venezuelan education, even if his name does not always appear in the great school pantheons. His books educated thousands of Latin American children and young people, and his legacy is almost comparable to that of the greatest thinkers of the XIX century. While Bolivar gave his sword for the liberation of the Patria Grande, and Martí gave his thought, Luis Felipe Mantilla contributed grammar. His work built a silent bridge between the two countries.

Luis Felipe Mantilla, of Spanish descent, was born in Havana in 1833. He studied at the University of Seville and then returned to Cuba to devote himself to teaching and to advancing public education. In Havana, he was a professor at the Colegio del Salvador de Luz, founded by the eminent Cuban educator Jose de la Luz y Caballero.

It is not hard to imagine him standing before the same classrooms through which other Cuban heroes once passed, such as the mambi fighters Ignacio Agramonte and the brothers Manuel and Julio Sanguily. Historians say that for Mantilla it was not enough to want a free nation; one had to master language in order to exercise freedom. And it was his pro-independence leanings that forced Mantilla to leave the country in 1852, at the age of 19.

That year, he traveled to the United States, where he also worked as a professor at New York University. That leap from the Caribbean to the North would trace the intimate map of his life, with education as a homeland he carried wherever he went.

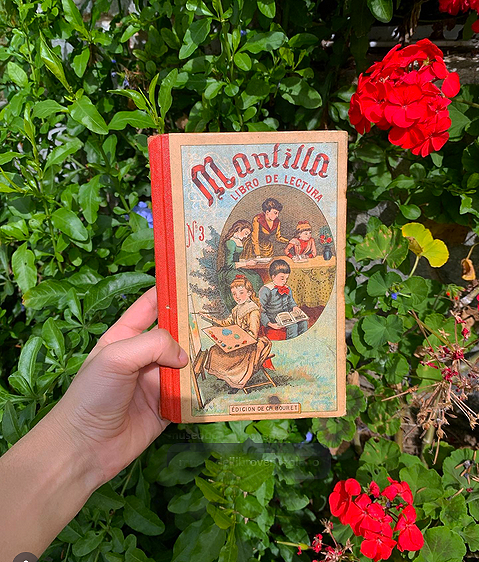

In 1866, in Paris, the Spanish Bookstore of Garnier Brothers published his book for the first time, conceived to spread teaching methods friendly to the Spanish language. The central work was issued in three volumes under the title Libros de Lectura (Reading Books), but it was widely known as El Mantilla.

Over time it would have multiple editions, reprints, and transnational circulation, so much so that it continued to be republished in several Latin American countries, especially in Venezuela. In those pages, pedagogy becomes a mechanism: letters and sounds; then syllables; then words; then phrases and sentences tied to everyday life. The goal was simple but ambitious: to ensure that the beginner reader acquired real fluency.

He died in New York in 1878, at 45, without suspecting that El Mantilla would change the course of education in Latin America.

The same history, and the word as a bridge

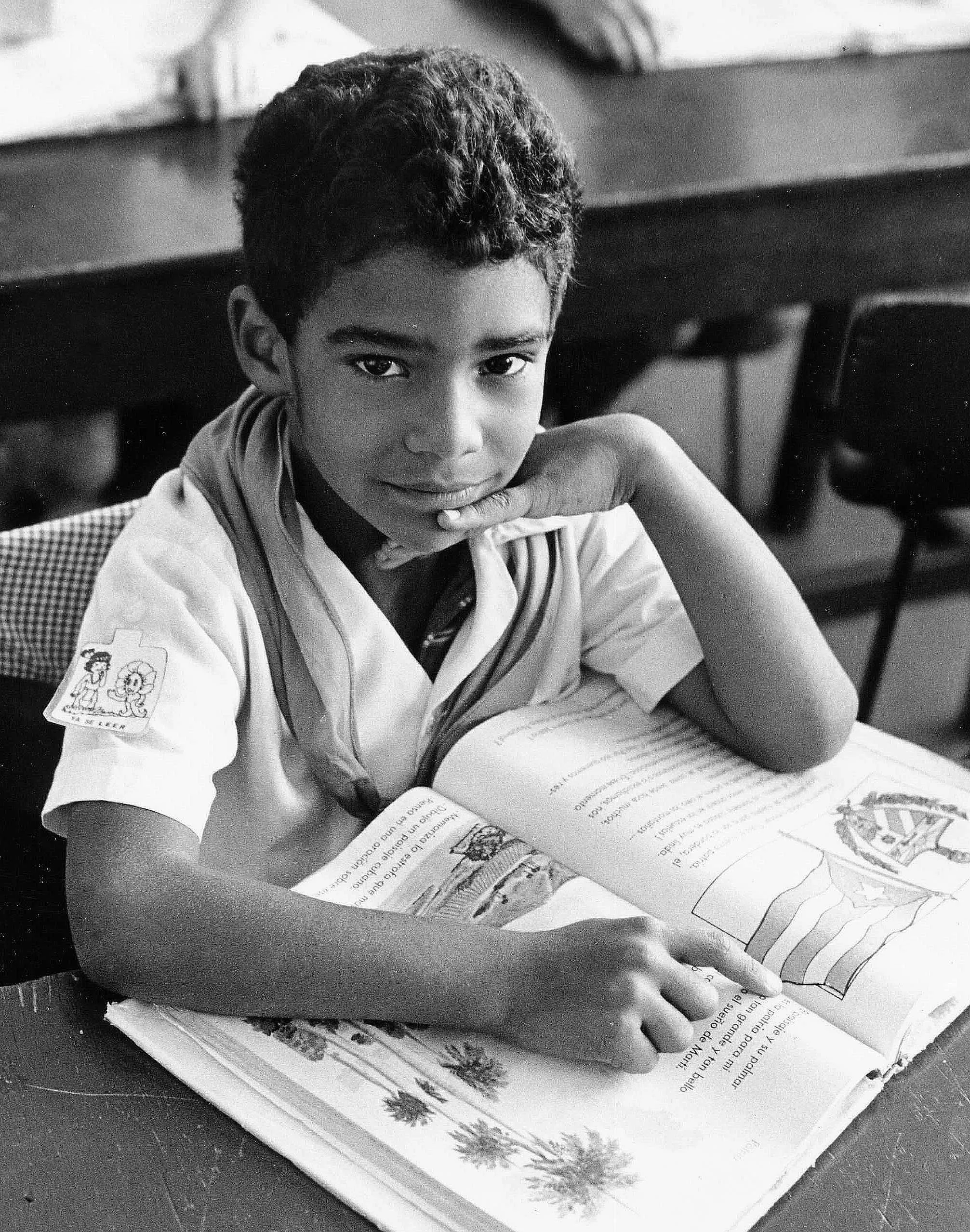

In working-class Caracas in the 1950s, marked by families newly arrived from the countryside, tight incomes, and almost no formal preschool system, home-based teachers emerged, turning living rooms into classrooms and charging barely one bolivar a week to teach using El Mantilla method.

Literacy happened wherever it could: in a dining room, in a free corner, on the table where lunch was also served. “The living room filled with little kids from the neighborhood, with their small chairs on their shoulders, and there they spent much of the morning following the teacher’s precise and strict instructions. She wouldn’t tolerate rochelitas (noise and silliness)… m-a, ma, m-a, ma, what does it say: mama (mom). Just as it appeared in the original text,” recounts historian Luis Martín in his article “Las maestras de las primeras edades,” published on the Diario de Caracas portal.

For many low-income children, that living room was the gateway to school. They left ready for first grade, “reading, writing, and doing basic arithmetic.” The Libro Mantilla was sold even in hardware stores, at affordable prices. Even so, some children did not have it because their parents could not buy it even at the lowest price. So a handmade notebook was improvised, with drawings, alphabets, and copied phrases.

In those small improvised little schools, you can see the true reach of El Mantilla and the invisible bridge that ties Havana and Caracas, one that endures to this day, though in other forms. El Mantilla was the prelude to the Yo,Si Puedo mission launched in 2003, which made it possible for Venezuela to declare itself free of illiteracy in 2005. Two centuries apart, one certainty remains: Cuba and Venezuela share the same history, with education as their bridge.

And that bridge does not diminish, especially in this time of crisis for both countries.

Alejandra Garcia is a Latin American correspondent for Resumen Latinoamericano and an evening anchor for Telesur evening news in English.

Source: Resumen Latinoamericano – US

Join the Struggle-La Lucha Telegram channel