Bob McCubbin (1942-2025) was a pioneering revolutionary theorist and activist. In 1976, he wrote one of the first Marxist analyses of LGBTQ+ oppression. His book “The Gay Question: A Marxist Appraisal,” later expanded as “The Roots of Lesbian & Gay Oppression,” was groundbreaking. The Stonewall Rebellion shaped his politics. He fought for LGBTQ+ liberation for five decades. He stood with the Black Liberation movement. He marched in the streets. He organized strikes. A co-founder of the Struggle for Socialism Party in 2018, he wrote until the end, publishing “The Social Evolution of Humanity, Marx and Engels Were Right!” in his final years. He organized for Palestine at San Diego Pride just months before his death. McCubbin died in August 2025 at age 83.

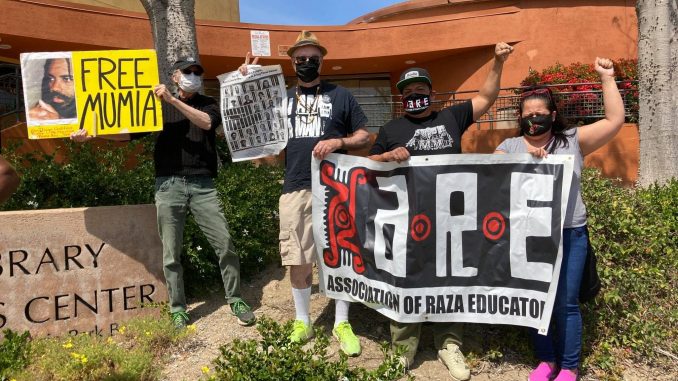

The following paper is by Dawn Miller. She is a teacher in San Diego and a member of the Association of Raza Educators. She wrote this several years ago. It spotlights Bob McCubbin as a local activist, organizer, and mentor. McCubbin supported the Association of Raza Educators for years. He championed their mission. He embodied what it means to be a teacher of and for the people.

No Pride Without Labor:

The Revolutionary Bond Between Queer and Working-Class Liberation

In the mid-1990s, fresh out of college, I had the unforgettable experience of meeting Leslie Feinberg, managing editor of Workers World newspaper and legendary “Transgender Warrior,” speak at a local event. I was brought there by Bob McCubbin, a close friend of Leslie’s and a fierce activist in his own right and fellow educator. I had never heard anyone articulate the intersections of oppression under capitalism as powerfully and clearly as Leslie did that day.

That moment, and Bob’s subsequent mentorship and writings, fundamentally shifted my own trajectory and politicization as a queer person. He helped me understand that the fight against queer oppression is inseparable from the fight against capitalism, and that true liberation for all oppressed peoples demands the advancement of communism and nothing less.

Tragically, Leslie has since passed, but I’ve had the great privilege of building a relationship with Bob, who is not only part of this paper’s focus but has also been a guiding figure in my ongoing understandings of radical queer and labor histories. Through my interviews with Bob, a pattern has become strikingly clear: Over the last century, there have been deep, deliberate acts of solidarity between the gay liberation movement and the labor movement. These moments of cooperation, though often under-recognized, were mutually beneficial, and in many cases, they created key openings for queer advancement within broader struggles for justice.

Now in his 70s, Bob’s class consciousness was honed at the young age of 10, working as a paper delivery boy to supplement his family’s income in 1940s Buffalo, New York. Working through high school and college, post-graduation, Bob found himself as part of Local 1199, an independent, progressive union that organized clerical workers at Columbia University. He remarks:

“The pay was terrible, and when we would make wage demands on the administration, their position was that we should be happy with the prestige we gained being associated with such a renowned institution. Our reply was always, ‘We cannot eat prestige.’”

Despite its anti-Vietnam war stance and massive mobilizations around social issues of the day, the union remained silent on sexual minority rights. Bob said he felt others knew and accepted his sexuality as a gay man, and he described the chapter as having an uncommonly large LGBTQ membership; however, the push for anti-discriminatory practices and clauses in contracts for queer unit members were not topics on the table yet.

Queer people have always been part of the labor movement: paying dues, organizing strikes, holding the line, and fighting tooth and nail as some of labor’s most outspoken organizers against capitalist exploitation. But for decades, their identities were buried, forced into silence by the same systems that demanded their labor while denying their humanity.

In the 1930s, the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union of the CIO deliberately organized gay workers and promoted them into union leadership, but this was an anomaly. There are a few documented examples of labor’s push for LGBTQ rights peppering the ‘50s and early ‘60s, but most unions remained complicit in erasing queer members, offering little protection as these workers faced surveillance, firings and blatant violence simply for existing.

It wasn’t until the rebellion at Stonewall in 1969, an uprising led by working-class, Black and Brown trans and queer people, that the labor movement began to feel the pressure to confront its own failures and step up. Queer workers demanded that labor reckon with the truth: There’s no liberation for the working class without queer liberation, and there is no revolution worth fighting for that leaves anyone behind.

Bob told of life as a gay man in 1970 New York, where police would come regularly to the gay clubs, which were then illegal, and, “with pure hate in their eyes,” harass, defile, assault, and arrest the men at their whim.

In one incident, Bob recalled the police shooting of a young gay man who was hospitalized with life-threatening injuries. When gay activists approached the young man about organizing a picket and protest against police brutality, he pleaded against it with great desperation for fear of further retaliation in the community at the hands of the cops. He did request help with his mounting hospital bills, and so Bob and friends organized a fundraiser dance, and the only venue that would hold their event was the meeting hall of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union of San Francisco.

Bob recalled sitting with the union leadership that night, all white, older men, “You could tell that although they were a bit surprised by the crowd that flitted around them, they were committed to their progressive philosophies and belief in solidarity with all workers in pursuit of a more just world.”

What began as a single meeting grew into a long-standing relationship rooted in mutual support and collaboration. It also underscores an often-overlooked historical truth: During a time when civil rights struggles were gaining traction, gay liberation remained deeply stigmatized, and unions were often one of the few, and sometimes the only, institutions willing to stand in solidarity with queer people and their struggle for justice.

In the mid-1970s, the gay community in California initiated a boycott of Coors Beer Company because it had fired a number of gay workers and forced new hires to submit to lie detector tests that questioned them about their sexual orientation. The boycott quickly spread to the East Coast and gained momentum as gay bars and gay-owned businesses bi-coastally refused to sell Coors products. Teamsters, who had also been planning a boycott because of unfair employment practices at Coors, approached gay organizers, specifically Harvey Milk and Howard Wallace, wanting to support and merge together to form a larger boycott. Milk and Howard insisted that the union be open to hiring gay folks as truck drivers; the union agreed, and a great moment of coalition building began.

With the backing of the nation’s largest union, not only was the boycott ultimately successful, but discriminatory employment tactics against gays and lesbians became part of the larger societal conversation around labor rights and civil rights for the LGBTQ community. The union went on to support Harvey Milk in a successful bid for San Francisco supervisor. Ultimately, the successes were evidence of the power of collaboration and the need for interdependence between labor and queer movements.

Back at Columbia, in the wake of Stonewall, Bob and fellow gay workers were ready for action. In the ensuing protests that followed Stonewall, the call to action from gay liberation leaders for the gay community to rise up, was heard loud and clear by Bob and his comrades. During a larger strike at Columbia University for wage increases, the gay contingent insisted the union also push for contract protection for “sexual minorities.” Having been originally organized by the Communist Party, the Columbia University chapter of Local 1199 was tolerant of its gay contingent, but had yet to push for specific rights.

As Bob recalled, “As progressive as it was, the Communist Party organizer and bargaining chair was rather cynical about our rank-and-file demand that protection for our LGBTQ members be included in the contract we were negotiating. At the ratification meeting, I asked him directly if we’d won inclusion of the clause. ‘Yes,’ he replied with a smirk, ‘we won protection for gays, bisexuals, trisexuals. …whatever.’”

Bob believes that this clause in the contract may in fact have been one of the first times such a labor right for the queer community was won, but lamented that, “the only place it’s documented would be in a dusty file cabinet somewhere on West 43rd Street.”

Gay rights activists and labor continued in collaborative struggle in 1978 with the introduction of the Briggs Initiative (Proposition 6) in California, which would have banned “homosexuals” from teaching in the public schools. The AFL-CIO came out in full support to defeat the proposition, spending large amounts of money and sending out massive amounts of anti-6 literature.

Importantly, during this campaign, the AFL-CIO pushed for a federal law banning discrimination based on sexual orientation. Although this legislation was never realized, and LGBTQ workers today still lack federal protection, the labor-gay alliance was successful in defeating the Briggs Initiative and further bolstered the relationship between the groups that laid ground for future successes.

As Gerald Hunt elaborates in his book “Laboring for Rights: Unions and Sexual Diversity Across Nations,” “During the 1990s, as with California’s Briggs Initiative in 1978, union backing at the national, state and local levels was critical in defeating anti-gay initiatives and amendments in Oregon, Washington and Idaho” (82). He goes on to tell of anti-gay campaigns that were successful in places where labor was absent or late to respond to calls for support.

Throughout the history of the gay community’s struggle for liberation, labor has often been its strongest, loudest and most consistent ally. Alliances in times of struggle, on both sides, have proven advantageous, and principles of solidarity have advanced success for all involved. However, today, in a time of great attacks on labor, some critics ask where the voice and support of the gay community has gone. While gay people enjoy greater rights and more social advancement than ever before, that same community is largely silent as labor unions and workers’ rights are systematically decimated.

Author Jerame Davis writes, “If we cannot stand in solidarity with one of our oldest supporters, what is the message we are sending to the myriad of allies we’re creating today? Are we simply opportunistic friends whose relationship depends on what the other side has to offer and nothing more? Solidarity isn’t transactional, it’s transformational.”

It was Bob’s early experiences in both union work and the emerging gay liberation movement that launched him into a lifelong path as a radical organizer, prolific writer and dedicated comrade in the Workers World Party. For Bob, the solidarity he witnessed in the labor and queer movements was a political awakening. It shaped his fundamental understanding that race, gender, class and sexuality aren’t separate issues; they’re deeply entangled fronts in the same war against capitalist oppression. His analysis exposes the systems designed to divide us and insists that only through collective, intersectional struggle can liberation be won.

During one of our conversations, Bob cried as he recalled listening to the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg on the radio as a child. He wept not only from the memory of that brutal, largely forgotten attack on the labor and leftist movements of the time, but from having lived long enough to see many of the hard-fought victories for labor and queer rights now being eroded before his eyes. And yet, despite having witnessed both monumental gains and devastating setbacks, Bob remains resolute.

“I’m humbled to have once seen a bright light shining, to have known and lived the meaning of true revolutionary solidarity,” he told me. “I was ready then, and I remain ready now, to tackle oppression, in all its forms, at every turn.”

Join the Struggle-La Lucha Telegram channel