For most of U.S. history, general strikes have been rare — not because workers lacked the will to fight, but because the ruling class moved quickly and violently whenever that power surfaced.

When workers across an entire city stop work together, they do more than make demands. They expose who actually keeps society running, and that revelation has repeatedly been met with repression: police violence, mass arrests, court injunctions, federal intervention, and laws written to make such actions illegal before they can spread.

That history is no longer abstract. On Jan. 7, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent Jonathan Ross shot and killed Renee Good, a 37-year-old lesbian mother and U.S. citizen, on a residential Minneapolis street. Good had been observing ICE operations near her home after dropping her six-year-old son at school.

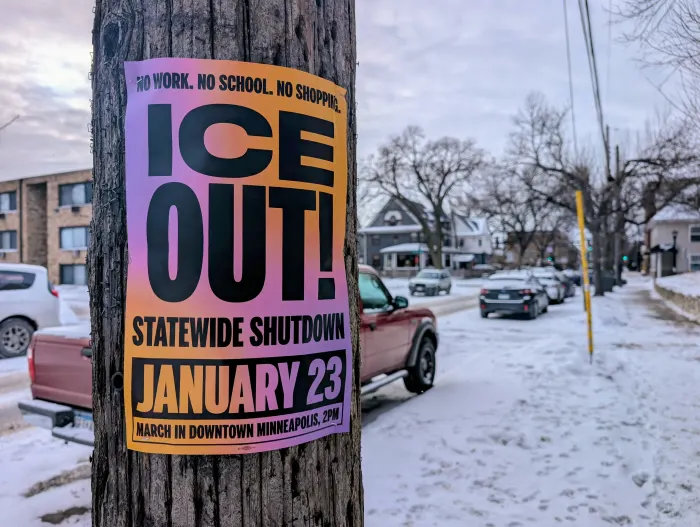

In the days since, federal agents have been filmed violently detaining protesters and bystanders. In response, a coalition of Minneapolis community organizations, immigrant defense groups, and labor unions has called for a citywide mass action on Jan. 23 — a day of no work, no school, no shopping — demanding that ICE leave the city.

More than 90 organizations have endorsed the “ICE Out of Minnesota: Day of Truth & Freedom” call for no work/school/shopping Friday, Jan. 23.

Union endorsers include: Minneapolis Regional Labor Federation AFL-CIO, ATU Local 1005, SEIU Local 26, UNITE HERE Local 17, CWA Local 7250, St. Paul Federation of Educators Local 28, Minneapolis Federation of Educators AFT Local 59, IATSE Local 13, Graduate Labor Union, and UE Local 1105.

If large numbers of workers withhold their labor across the city on that day, the action would amount to a general strike.

Renee Good was white and a U.S. citizen. She was not the target of an immigration arrest and was not accused of any crime. Her killing came amid a sharp escalation of immigration enforcement violence under the Trump administration’s second term — violence that has overwhelmingly targeted immigrants and people of color. In 2025 alone, 31 people died in ICE custody, the highest number in more than two decades. In the first days of 2026, several more followed. For years, authorities treated such federal repression as routine while it remained directed at immigrants and communities of color.

The general strike

The general strike — workers across an entire city or region stopping work simultaneously — represents one of the most powerful weapons in the working-class arsenal. It is also one of the rarest in U.S. history.

That rarity has nothing to do with a lack of militancy. U.S. workers have repeatedly shown a willingness to fight. What makes general strikes exceptional is their scope: they are mass actions, drawing in workers across industries, workplaces, and neighborhoods at the same time.

When labor is withdrawn on that scale, it disrupts not just individual employers but the normal functioning of an entire city or region.

That is precisely why such actions provoke a harsh response. In the United States, strikes are routinely met with police violence, mass arrests, injunctions, and federal intervention. Sympathy strikes and secondary actions have been criminalized, and even legally permitted strikes are hemmed in by court orders and enforcement powers designed to contain them.

The United States is the most undemocratic of the world’s top industrialized imperialist powers when it comes to labor — workers have few rights, and even those few are routinely suppressed.

Seattle 1919: The high-water mark

The Seattle General Strike of February 1919 remains the largest general strike in U.S. history. For five days, 65,000 workers shut down the city. Shipyard workers had walked out for higher wages; within days, the entire Seattle labor movement joined them in solidarity.

The action was coordinated by unions, but its scope quickly exceeded any single organization’s control. What followed was later known as a general strike.

Workers did not simply stop working—they organized to keep the city running on their own terms. Union-run milk stations ensured deliveries to hospitals and families with infants. Labor guards maintained order without police. Cafeterias fed thousands of workers each day.

Yet the strike ended without winning its original demands. The strike committee faced immediate hostility from the federal government, the press, and national AFL officials. Seattle’s mayor denounced the strikers as Bolsheviks in the wake of the Russian Revolution. Federal troops were mobilized. Pressure mounted to return to work.

Crucially, the strike lacked specific, achievable demands beyond solidarity with the shipyard workers. When the shipyard dispute stalled, the General Strike Committee voted to end the action. Workers returned without concessions — but they had demonstrated something that terrified the ruling class: For five days, workers shut down a major U.S. city and ran it themselves. That demonstration shaped the repression that followed.

San Francisco 1934: When police violence sparks mass action

Fifteen years later, San Francisco showed a different dynamic. The 1934 General Strike grew out of a two-month West Coast longshore strike that had already paralyzed Pacific ports. On July 5 — “Bloody Thursday” — police opened fire on picketers, killing two workers.

Outrage swept the city. Within days, up to 150,000 workers walked out.

In San Francisco, police killings transformed a bitter but contained struggle into a citywide shutdown. When violence by police and government forces becomes impossible to ignore, anger that has been building for years can break into open, collective action.

The strike differed from Seattle in key ways. It grew out of an ongoing fight with clear demands: union recognition for longshore workers and an end to the “shape-up” hiring system. Workers had already endured months of confrontation. They had leadership tested in struggle and rank-and-file support prepared for escalation.

The National Guard occupied the waterfront. Hundreds were arrested. But after four days, workers won. Arbitration granted union recognition and established the hiring hall, shifting power on the docks for generations.

Minneapolis’s demand — ICE out of the city — is similarly clear. But it targets federal power rather than an employer.

As Chris Silvera, the longest-serving principal officer in the Teamsters and former chairperson of the Teamsters National Black Caucus, has emphasized in his address “1934: A Year of Good Trouble,” the San Francisco General Strike was not an isolated eruption.

It was part of a broader working-class upheaval during the depths of the Great Depression — from the Toledo Auto-Lite strike to the Minneapolis Teamsters’ strikes and the coast-wide longshore shutdown. With unemployment soaring, banks collapsing, and entire cities thrown into crisis, violence by police and federal authorities in 1934 did not contain these struggles; it accelerated them, turning strikes that began in single industries into citywide confrontations that reshaped the labor movement for decades.

In 1934, Minneapolis was transformed by police violence into a center of mass labor revolt; in 2026, it is once again testing how police and federal repression reshapes collective response.

Oakland 1946: How the strike was shut down from above

The Oakland General Strike of December 1946 began with women department-store workers. Police escorted scab trucks through picket lines at two downtown stores where women clerks had been on strike for weeks. Outrage spread quickly.

Workers across Oakland walked out spontaneously — 130,000 in a city of about 400,000. Downtown became a workers’ festival, with jukeboxes dragged into the streets and bars offering free drinks to strikers.

The Oakland General Strike of December 1946 shows how quickly mass action can be demobilized when officials step in to contain it.

The strike showed how quickly rank-and-file solidarity can spread across a city — and how quickly it can be cut off when union officials intervene to protect their own authority and position, even if that means ending a struggle workers themselves started.

Why general strikes disappeared

The strike wave of the 1930s and 1940s terrified the ruling class. Their response was systematic.

The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 banned sympathy strikes, secondary boycotts, and mass picketing — the very tactics that had made general strikes possible. It required union officials to sign anti-communist affidavits, driving militants and left-wing organizers out of unions.

The Cold War completed the process. What replaced class-struggle unionism was “business unionism”: unions reduced to negotiating contracts, policing their own members, and maintaining institutional stability, rather than mobilizing workers as a class against employers and the government.

The result was more than seven decades without a general strike in any U.S. city.

2006: Mass action without structure

The 2006 “Day Without Immigrants” showed that mass work stoppages were still possible in the United States — and also showed their limits when they are not backed by durable organization.

On May 1, 2006, millions of immigrant workers and their supporters stayed home from work or walked out across the country to protest the Sensenbrenner bill, which would have criminalized undocumented immigrants and those who assisted them. Meatpacking plants shut down or slowed across the Midwest. Construction sites across the Southwest and California were deserted. Restaurants, hotels, garment shops, and food-processing facilities closed or operated with skeleton crews. In cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, Dallas, and Denver, marches drew hundreds of thousands, in some cases more than a million people.

For a single day, the action made something unmistakably clear: Immigrant labor is central to the U.S. economy, and when that labor is withdrawn, entire industries feel it immediately.

But the action was not rooted in workplace organization or strike committees. It was called largely by coalitions of immigrant rights groups, churches, and Spanish-language media, not by unions prepared to sustain a work stoppage. When May 1 ended, most participants returned to work the next day. There was no coordinated escalation, no mechanism to defend participants from retaliation, and no organization capable of turning a one-day shutdown into sustained pressure.

The Sensenbrenner bill was eventually dropped, but broader demands — legalization, an end to raids, and full rights for immigrant workers — were never secured.

2018–2019: Teachers show another path

In 2018, teachers in West Virginia struck illegally. Public-sector workers there had no collective bargaining rights, and the state had not seen a major strike in decades. Educators shut down every public school in the state for nine days. With broad public support and workers refusing to return under pressure, the legislature approved a 5% raise — not only for teachers, but for all state workers.

The following year, teachers in Los Angeles struck for nine days, pressing demands that went beyond wages. They called for smaller class sizes, more nurses and counselors, and limits on charter school expansion. In Chicago, educators stayed out for 11 days, winning enforceable class-size caps, staffing increases, and protections for students facing housing insecurity and immigration enforcement.

These were sustained work stoppages carried out illegally, in defiance of labor law and political threats. They shut down school systems, disrupted daily life, and forced concessions. They were limited to a single sector, not citywide shutdowns.

What’s different now — and what Jan. 23 could mean

Any citywide work stoppage today faces formidable obstacles. Union density is lower. Legal repression is harsher. Workplaces are fragmented. Many workers lack formal collective bargaining rights.

Yet the Minneapolis call has emerged with notable strengths. It is broad from the start. It links labor action to opposition to police and federal repression. And it has drawn union endorsement without being limited by formal strike procedures.

Whether Jan. 23 remains a one-day action or opens onto something larger will be decided by what happens next.

History does confirm this much: When workers across a city stop work together, they demonstrate a power no other form of protest can match. That power terrifies those who benefit from workers remaining divided.

Renee Good was shot and killed by a United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent during a federal operation on Jan. 7, igniting widespread protests and public outcry. If Minneapolis workers withhold their labor together, they will be confronting a question the ruling class has long tried to suppress: What happens when working people decide they’ve had enough?