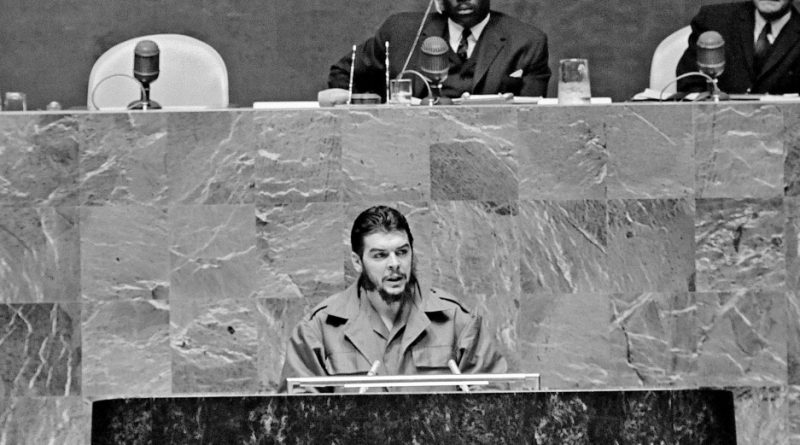

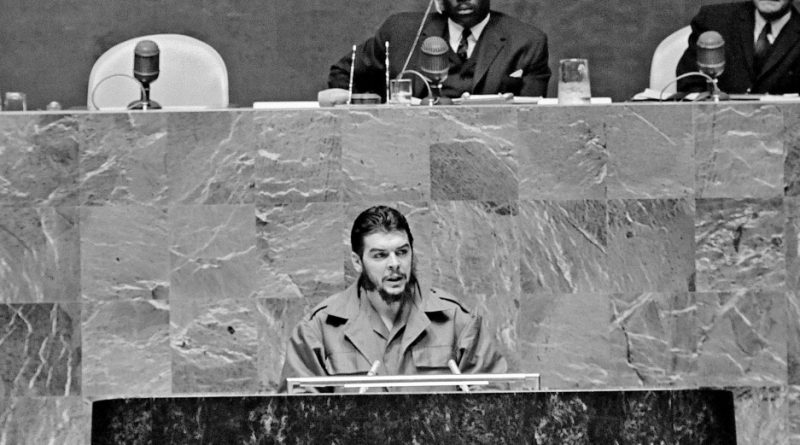

Mr. President;

Distinguished delegates:

The delegation of Cuba to this Assembly, first of all, is pleased to fulfill the agreeable duty of welcoming the addition of three new nations to the important number of those that discuss the problems of the world here. We, therefore, greet, in the persons of their presidents and prime ministers, the peoples of Zambia, Malawi, and Malta, and express the hope that from the outset these countries will be added to the group of Nonaligned countries that struggle against imperialism, colonialism, and neocolonialism.

We also wish to convey our congratulations to the president of this Assembly [Alex Quaison-Sackey of Ghana], whose elevation to so high a post is of special significance since it reflects this new historic stage of resounding triumphs for the peoples of Africa, who up until recently were subject to the colonial system of imperialism. Today, in their immense majority these peoples have become sovereign states through the legitimate exercise of their self-determination. The final hour of colonialism has struck, and millions of inhabitants of Africa, Asia, and Latin America rise to meet a new life and demand their unrestricted right to self-determination and to the independent development of their nations.

We wish you, Mr. President, the greatest success in the tasks entrusted to you by the member states.

Cuba comes here to state its position on the most important points of controversy and will do so with the full sense of responsibility that the use of this rostrum implies, while at the same time fulfilling the unavoidable duty of speaking clearly and frankly.

We would like to see this Assembly shake itself out of complacency and move forward. We would like to see the committees begin their work and not stop at the first confrontation. Imperialism wants to turn this meeting into a pointless oratorical tournament, instead of solving the serious problems of the world. We must prevent it from doing so. This session of the Assembly should not be remembered in the future solely by the number 19 that identifies it. Our efforts are directed to that end.

We feel that we have the right and the obligation to do so because our country is one of the most constant points of friction. It is one of the places where the principles upholding the right of small countries to sovereignty are put to the test day by day, minute by minute. At the same time, our country is one of the trenches of freedom in the world, situated a few steps away from U.S. imperialism, showing by its actions, its daily example, that in the present conditions of humanity the peoples can liberate themselves and can keep themselves free.

Of course, there now exists a socialist camp that becomes stronger day by day and has more powerful weapons of struggle. But additional conditions are required for survival: the maintenance of internal unity, faith in one’s own destiny, and the irrevocable decision to fight to the death for the defense of one’s country and revolution. These conditions, distinguished delegates, exist in Cuba.

Of all the burning problems to be dealt with by this Assembly, one of special significance for us, and one whose solution we feel must be found first — so as to leave no doubt in the minds of anyone — is that of peaceful coexistence among states with different economic and social systems. Much progress has been made in the world in this field. But imperialism, particularly U.S. imperialism, has attempted to make the world believe that peaceful coexistence is the exclusive right of the earth’s great powers. We say here what our president said in Cairo, and what later was expressed in the declaration of the Second Conference of Heads of State or Government of Nonaligned Countries: that peaceful coexistence cannot be limited to the powerful countries if we want to ensure world peace. Peaceful coexistence must be exercised among all states, regardless of size, regardless of the previous historical relations that linked them, and regardless of the problems that may arise among some of them at a given moment.

At present, the type of peaceful coexistence to which we aspire is often violated. Merely because the Kingdom of Cambodia maintained a neutral attitude and did not bow to the machinations of U.S. imperialism, it has been subjected to all kinds of treacherous and brutal attacks from the Yankee bases in South Vietnam.

Laos, a divided country, has also been the object of imperialist aggression of every kind. Its people have been massacred from the air. The conventions concluded at Geneva have been violated, and part of its territory is in constant danger of cowardly attacks by imperialist forces.

The Democratic Republic of Vietnam knows all these histories of aggression as do few nations on earth. It has once again seen its frontier violated, has seen enemy bombers and fighter planes attack its installations and U.S. warships, violating territorial waters, attack its naval posts. At this time, the threat hangs over the Democratic Republic of Vietnam that the U.S. warmongers may openly extend into its territory the war that for many years they have been waging against the people of South Vietnam. The Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China have given serious warnings to the United States. We are faced with a case in which world peace is in danger and, moreover, the lives of millions of human beings in this part of Asia are constantly threatened and subjected to the whim of the U.S. invader.

Peaceful coexistence has also been brutally put to the test in Cyprus, due to pressures from the Turkish Government and NATO, compelling the people and the government of Cyprus to make a heroic and firm stand in defense of their sovereignty.

In all these parts of the world, imperialism attempts to impose its version of what coexistence should be. It is the oppressed peoples in alliance with the socialist camp that must show them what true coexistence is, and it is the obligation of the United Nations to support them.

We must also state that it is not only in relations among sovereign states that the concept of peaceful coexistence needs to be precisely defined. As Marxists, we have maintained that peaceful coexistence among nations does not encompass coexistence between the exploiters and the exploited, between the oppressors and the oppressed. Furthermore, the right to full independence from all forms of colonial oppression is a fundamental principle of this organization. That is why we express our solidarity with the colonial peoples of so-called Portuguese Guinea, Angola, and Mozambique, who have been massacred for the crime of demanding their freedom. And we are prepared to help them to the extent of our ability in accordance with the Cairo declaration.

We express our solidarity with the people of Puerto Rico and their great leader, Pedro Albizu Campos, who, in another act of hypocrisy, has been set free at the age of 72, almost unable to speak, paralyzed, after spending a lifetime in jail. Albizu Campos is a symbol of the as-yet unfree but indomitable Latin America. Years and years of prison, almost unbearable pressures in jail, mental torture, solitude, total isolation from his people and his family, the insolence of the conqueror and its lackeys in the land of his birth — nothing broke his will. The delegation of Cuba, on behalf of its people, pays a tribute of admiration and gratitude to a patriot who confers honor upon our America.

The United States for many years has tried to convert Puerto Rico into a model of hybrid culture: the Spanish language with English inflections, the Spanish language with hinges on its backbone — the better to bow down before the Yankee soldier. Puerto Rican soldiers have been used as cannon fodder in imperialist wars, as in Korea, and have even been made to fire at their own brothers, as in the massacre perpetrated by the U.S. Army a few months ago against the unarmed people of Panama — one of the most recent crimes carried out by Yankee imperialism. And yet, despite this assault on their will and their historical destiny, the people of Puerto Rico have preserved their culture, their Latin character, their national feelings, which in themselves give proof of the implacable desire for independence lying within the masses on that Latin American island. We must also warn that the principle of peaceful coexistence does not encompass the right to mock the will of the peoples, as is happening in the case of the so-called British Guiana. There the government of Prime Minister Cheddi Jagan has been the victim of every kind of pressure and maneuver, and independence has been delayed to gain time to find ways to flout the people’s will and guarantee the docility of a new government, placed in power by covert means, in order to grant castrated freedom to this country of the Americas. Whatever roads Guiana may be compelled to follow to obtain independence, the moral and militant support of Cuba goes to its people.[15]

Furthermore, we must point out that the islands of Guadaloupe and Martinique have been fighting for a long time for self-government without obtaining it. This state of affairs must not continue. Once again we speak out to put the world on guard against what is happening in South Africa. The brutal policy of apartheid is applied before the eyes of the nations of the world. The peoples of Africa are compelled to endure the fact that on the African continent the superiority of one race over another remains official policy, and that in the name of this racial superiority murder is committed with impunity. Can the United Nations do nothing to stop this?

I would like to refer specifically to the painful case of the Congo, unique in the history of the modern world, which shows how, with absolute impunity, with the most insolent cynicism, the rights of peoples can be flouted. The direct reason for all this is the enormous wealth of the Congo, which the imperialist countries want to keep under their control. In the speech he made during his first visit to the United Nations, compañero Fidel Castro observed that the whole problem of coexistence among peoples boils down to the wrongful appropriation of other peoples’ wealth. He made the following statement: “End the philosophy of plunder and the philosophy of war will be ended as well.”

But the philosophy of plunder has not only not been ended, it is stronger than ever. And that is why those who used the name of the United Nations to commit the murder of Lumumba are today, in the name of the defense of the white race, murdering thousands of Congolese. How can we forget the betrayal of the hope that Patrice Lumumba placed in the United Nations? How can we forget the machinations and maneuvers that followed in the wake of the occupation of that country by UN troops, under whose auspices the assassins of this great African patriot acted with impunity? How can we forget, distinguished delegates, that the one who flouted the authority of the UN in the Congo — and not exactly for patriotic reasons, but rather by virtue of conflicts between imperialists — was Moise Tshombe, who initiated the secession of Katanga with Belgian support? And how can one justify, how can one explain, that at the end of all the United Nations’ activities there, Tshombe, dislodged from Katanga, should return as lord and master of the Congo? Who can deny the sad role that the imperialists compelled the United Nations to play?[16]

To sum up: dramatic mobilizations were carried out to avoid the secession of Katanga, but today Tshombe is in power, the wealth of the Congo is in imperialist hands — and the expenses have to be paid by the honorable nations. The merchants of war certainly do good business! That is why the government of Cuba supports the just stance of the Soviet Union in refusing to pay the expenses for this crime.

And as if this were not enough, we now have flung in our faces these latest acts that have filled the world with indignation. Who are the perpetrators? Belgian paratroopers, carried by U.S. planes, who took off from British bases. We remember as if it were yesterday that we saw a small country in Europe, a civilized and industrious country, the Kingdom of Belgium, invaded by Hitler’s hordes. We were embittered by the knowledge that this small nation was massacred by German imperialism, and we felt affection for its people. But this other side of the imperialist coin was the one that many of us did not see. Perhaps the sons of Belgian patriots who died defending their country’s liberty are now murdering in cold blood thousands of Congolese in the name of the white race, just as they suffered under the German heel because their blood was not sufficiently Aryan. Our free eyes open now to new horizons and can see what yesterday, in our condition as colonial slaves, we could not observe: that “Western Civilization” disguises behind its showy facade a picture of hyenas and jackals. That is the only name that can be applied to those who have gone to fulfill such “humanitarian” tasks in the Congo. A carnivorous animal that feeds on unarmed peoples. That is what imperialism does to men. That is what distinguishes the imperial “white man.”

All free men of the world must be prepared to avenge the crime of the Congo. Perhaps many of those soldiers, who were turned into sub-humans by imperialist machinery, believe in good faith that they are defending the rights of a superior race. In this Assembly, however, those peoples whose skins are darkened by a different sun, colored by different pigments, constitute the majority. And they fully and clearly understand that the difference between men does not lie in the color of their skin, but in the forms of ownership of the means of production, in the relations of production. The Cuban delegation extends greetings to the peoples of Southern Rhodesia and South-West Africa, oppressed by white colonialist minorities; to the peoples of Basutoland, Bechuanaland, Swaziland, French Somaliland, the Arabs of Palestine, Aden and the Protectorates, Oman; and to all peoples in conflict with imperialism and colonialism. We reaffirm our support to them.

I express also the hope that there will be a just solution to the conflict facing our sister republic of Indonesia in its relations with Malaysia. Mr. President: One of the fundamental themes of this conference is general and complete disarmament. We express our support for general and complete disarmament. Furthermore, we advocate the complete destruction of all thermonuclear devices and we support the holding of a conference of all the nations of the world to make this aspiration of all people a reality. In his statement before this assembly, our prime minister warned that arms races have always led to war. There are new nuclear powers in the world, and the possibilities of a confrontation are growing. We believe that such a conference is necessary to obtain the total destruction of thermonuclear weapons and, as a first step, the total prohibition of tests. At the same time, we have to establish clearly the duty of all countries to respect the present borders of other states and to refrain from engaging in any aggression, even with conventional weapons.

In adding our voice to that of all the peoples of the world who ask for general and complete disarmament, the destruction of all nuclear arsenals, the complete halt to the building of new thermonuclear devices and of nuclear tests of any kind, we believe it necessary to also stress that the territorial integrity of nations must be respected and the armed hand of imperialism held back, for it is no less dangerous when it uses only conventional weapons. Those who murdered thousands of defenseless citizens of the Congo did not use the atomic bomb. They used conventional weapons. Conventional weapons have also been used by imperialism, causing so many deaths.

Even if the measures advocated here were to become effective and make it unnecessary to mention it, we must point out that we cannot adhere to any regional pact for denuclearization so long as the United States maintains aggressive bases on our own territory, in Puerto Rico, Panama and in other Latin American states where it feels it has the right to place both conventional and nuclear weapons without any restrictions. We feel that we must be able to provide for our own defense in the light of the recent resolution of the Organization of American States against Cuba, on the basis of which an attack may be carried out invoking the Rio Treaty.[17] If the conference to which we have just referred were to achieve all these objectives — which, unfortunately, would be difficult — we believe it would be the most important one in the history of humanity. To ensure this it would be necessary for the People’s Republic of China to be represented, and that is why a conference of this type must be held. But it would be much simpler for the peoples of the world to recognize the undeniable truth of the existence of the People’s Republic of China, whose government is the sole representative of its people, and to give it the seat it deserves, which is, at present, usurped by the gang that controls the province of Taiwan, with U.S. support.

The problem of the representation of China in the United Nations cannot in any way be considered as a case of a new admission to the organization, but rather as the restoration of the legitimate rights of the People’s Republic of China.

We must repudiate energetically the “two Chinas” plot. The Chiang Kai-shek gang of Taiwan cannot remain in the United Nations. What we are dealing with, we repeat, is the expulsion of the usurper and the installation of the legitimate representative of the Chinese people.

We also warn against the U.S. Government’s insistence on presenting the problem of the legitimate representation of China in the UN as an “important question,” in order to impose a requirement of a two-thirds majority of members present and voting. The admission of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations is, in fact, an important question for the entire world, but not for the machinery of the United Nations, where it must constitute a mere question of procedure. In this way justice will be done. Almost as important as attaining justice, however, would be the demonstration, once and for all, that this august Assembly has eyes to see, ears to hear, tongues to speak with and sound criteria for making its decisions. The proliferation of nuclear weapons among the member states of NATO, and especially the possession of these devices of mass destruction by the Federal Republic of Germany, would make the possibility of an agreement on disarmament even more remote, and linked to such an agreement is the problem of the peaceful reunification of Germany. So long as there is no clear understanding, the existence of two Germanys must be recognized: that of the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic. The German problem can be solved only with the direct participation in negotiations of the German Democratic Republic with full rights. We shall only touch on the questions of economic development and international trade that are broadly represented in the agenda. In this very year of 1964 the Geneva conference was held at which a multitude of matters related to these aspects of international relations were dealt with. The warnings and forecasts of our delegation were fully confirmed, to the misfortune of the economically dependent countries.

We wish only to point out that insofar as Cuba is concerned, the United States of America has not implemented the explicit recommendations of that conference, and recently the U.S. Government also prohibited the sale of medicines to Cuba. By doing so it divested itself, once and for all, of the mask of humanitarianism with which it attempted to disguise the aggressive nature of its blockade against the people of Cuba.

Furthermore, we state once more that the scars left by colonialism that impede the development of the peoples are expressed not only in political relations. The so-called deterioration of the terms of trade is nothing but the result of the unequal exchange between countries producing raw materials and industrial countries, which dominate markets and impose the illusory justice of equal exchange of values.

So long as the economically dependent peoples do not free themselves from the capitalist markets and, in a firm bloc with the socialist countries, impose new relations between the exploited and the exploiters, there will be no solid economic development. In certain cases there will be retrogression, in which the weak countries will fall under the political domination of the imperialists and colonialists.

Finally, distinguished delegates, it must be made clear that in the area of the Caribbean, manoeuvres and preparations for aggression against Cuba are taking place, on the coasts of Nicaragua above all, in Costa Rica as well, in the Panama Canal Zone, on Vieques Island in Puerto Rico, in Florida and possibly in other parts of U.S. territory and perhaps also in Honduras. In these places Cuban mercenaries are training, as well as mercenaries of other nationalities, with a purpose that cannot be the most peaceful one. After a big scandal, the government of Costa Rica — it is said — has ordered the elimination of all training camps of Cuban exiles in that country.

No one knows whether this position is sincere, or whether it is a simple alibi because the mercenaries training there were about to commit some misdeed. We hope that full cognizance will be taken of the real existence of bases for aggression, which we denounced long ago, and that the world will ponder the international responsibility of the government of a country that authorizes and facilitates the training of mercenaries to attack Cuba. We should note that news of the training of mercenaries in different parts in the Caribbean and the participation of the U.S. Government in such acts is presented as completely natural in the newspapers in the United States. We know of no Latin American voice that has officially protested this. This shows the cynicism with which the U.S. Government moves its pawns.

The sharp foreign ministers of the OAS had eyes to see Cuban emblems and to find “irrefutable” proof in the weapons that the Yankees exhibited in Venezuela, but they do not see the preparations for aggression in the United States, just as they did not hear the voice of President Kennedy, who explicitly declared himself the aggressor against Cuba at Playa Girón [Bay of Pigs invasion of April 1961]. In some cases, it is a blindness provoked by the hatred against our revolution by the ruling classes of the Latin American countries. In others — and these are sadder and more deplorable — it is the product of the dazzling glitter of mammon.

As is well known, after the tremendous commotion of the so-called Caribbean crisis, the United States undertook certain commitments with the Soviet Union. These culminated in the withdrawal of certain types of weapons that the continued acts of aggression of the United States — such as the mercenary attack at Playa Girón and threats of invasion against our homeland — had compelled us to install in Cuba as an act of legitimate and essential defense.

The United States, furthermore, tried to get the UN to inspect our territory. But we emphatically refuse, since Cuba does not recognize the right of the United States, or of anyone else in the world, to determine the type of weapons Cuba may have within its borders.

In this connection, we would abide only by multilateral agreements, with equal obligations for all the parties concerned. As Fidel Castro has said: “So long as the concept of sovereignty exists as the prerogative of nations and of independent peoples, as a right of all peoples, we will not accept the exclusion of our people from that right. So long as the world is governed by these principles, so long as the world is governed by those concepts that have universal validity because they are universally accepted and recognized by the peoples, we will not accept the attempt to deprive us of any of those rights, and we will renounce none of those rights.” The Secretary-General of the United Nations, U Thant, understood our reasons. Nevertheless, the United States attempted to establish a new prerogative, an arbitrary and illegal one: that of violating the airspace of a small country. Thus, we see flying over our country U-2 aircraft and other types of spy planes that, with complete impunity, fly over our airspace. We have made all the necessary warnings for the violations of our airspace to cease, as well as for a halt to the provocations of the U.S. Navy against our sentry posts in the zone of Guantánamo, the buzzing by aircraft of our ships or the ships of other nationalities in international waters, the pirate attacks against ships sailing under different flags, and the infiltration of spies, saboteurs and weapons onto our island.

We want to build socialism. We have declared that we are supporters of those who strive for peace. We have declared ourselves to be within the group of Nonaligned countries, although we are Marxist-Leninists, because the Nonaligned countries, like ourselves, fight imperialism. We want peace. We want to build a better life for our people. That is why we avoid, insofar as possible, falling into the provocations manufactured by the Yankees. But we know the mentality of those who govern them. They want to make us pay a very high price for that peace. We reply that the price cannot go beyond the bounds of dignity.

And Cuba reaffirms once again the right to maintain on its territory the weapons it deems appropriate, and its refusal to recognize the right of any power on earth — no matter how powerful — to violate our soil, our territorial waters, or our airspace.

If in any assembly Cuba assumes obligations of a collective nature, it will fulfill them to the letter. So long as this does not happen, Cuba maintains all its rights, just as any other nation. In the face of the demands of imperialism, our prime minister laid out the five points necessary for the existence of a secure peace in the Caribbean. They are:

1. A halt to the economic blockade and all economic and trade pressures by the United States, in all parts of the world, against our country.

2. A halt to all subversive activities, launching and landing of weapons and explosives by air and sea, organization of mercenary invasions, infiltration of spies and saboteurs, acts all carried out from the territory of the United States and some accomplice countries.

3. A halt to pirate attacks carried out from existing bases in the United States and Puerto Rico.

4. A halt to all the violations of our airspace and our territorial waters by U.S. aircraft and warships.

5. Withdrawal from the Guantánamo naval base and return of the Cuban territory occupied by the United States.”

None of these elementary demands has been met, and our forces are still being provoked from the naval base at Guantánamo. That base has become a nest of thieves and a launching pad for them into our territory. We would tire this Assembly were we to give a detailed account of the large number of provocations of all kinds. Suffice it to say that including the first days of December, the number amounts to 1,323 in 1964 alone. The list covers minor provocations such as violation of the boundary line, launching of objects from the territory controlled by the United States, the commission of acts of sexual exhibitionism by U.S. personnel of both sexes, and verbal insults. It includes others that are more serious, such as shooting off small caliber weapons, aiming weapons at our territory, and offenses against our national flag. Extremely serious provocations include those of crossing the boundary line and starting fires in installations on the Cuban side, as well as rifle fire. There have been 78 rifle shots this year, with the sorrowful toll of one death: that of Ramón López Peña, a soldier, killed by two shots fired from the U.S. post three and a half kilometers from the coast on the northern boundary. This extremely grave provocation took place at 7:07 p.m. on July 19, 1964, and the prime minister of our government publicly stated on July 26 that if the event were to recur he would give orders for our troops to repel the aggression. At the same time orders were given for the withdrawal of the forward line of Cuban forces to positions farther away from the boundary line and the construction of the necessary fortified positions. One thousand three hundred and twenty-three provocations in 340 days amount to approximately four per day. Only a perfectly disciplined army with a morale such as ours could resist so many hostile acts without losing its self-control.

Forty-seven countries meeting at the Second Conference of Heads of State or Government of Nonaligned Countries in Cairo unanimously agreed:

“Noting with concern that foreign military bases are in practice a means of bringing pressure on nations and retarding their emancipation and development, based on their own ideological, political, economic and cultural ideas, the conference declares its unreserved support to the countries that are seeking to secure the elimination of foreign bases from their territory and calls upon all states maintaining troops and bases in other countries to remove them immediately. The conference considers that the maintenance at Guantánamo (Cuba) of a military base of the United States of America, in defiance of the will of the government and people of Cuba and in defiance of the provisions embodied in the declaration of the Belgrade conference, constitutes a violation of Cuba’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Noting that the Cuban Government expresses its readiness to settle its dispute over the base at Guantánamo with the United States of America on an equal footing, the conference urges the U.S. Government to open negotiations with the Cuban Government to evacuate their base”.

The government of the United States has not responded to this request of the Cairo conference and is attempting to maintain indefinitely by force its occupation of a piece of our territory, from which it carries out acts of aggression such as those detailed earlier.

The Organization of American States — which the people also call the U.S. Ministry of Colonies — condemned us “energetically,” even though it had just excluded us from its midst, ordering its members to break off diplomatic and trade relations with Cuba. The OAS authorized aggression against our country at any time and under any pretext, violating the most fundamental international laws, completely disregarding the United Nations. Uruguay, Bolivia, Chile and Mexico opposed that measure, and the government of the United States of Mexico refused to comply with the sanctions that had been approved. Since then we have had no relations with any Latin American countries except Mexico, and this fulfills one of the necessary conditions for direct aggression by imperialism.

We want to make clear once again that our concern for Latin America is based on the ties that unite us: the language we speak, the culture we maintain, and the common master we had. We have no other reason for desiring the liberation of Latin America from the U.S. colonial yoke. If any of the Latin American countries here decide to reestablish relations with Cuba, we would be willing to do so on the basis of equality, and without viewing that recognition of Cuba as a free country in the world to be a gift to our government. We won that recognition with our blood in the days of the liberation struggle. We acquired it with our blood in the defense of our shores against the Yankee invasion.

Although we reject any accusations against us of interference in the internal affairs of other countries, we cannot deny that we sympathize with those people who strive for their freedom. We must fulfill the obligation of our government and people to state clearly and categorically to the world that we morally support and stand in solidarity with peoples who struggle anywhere in the world to make a reality of the rights of full sovereignty proclaimed in the UN Charter.

It is the United States that intervenes. It has done so historically in Latin America. Since the end of the last century Cuba has experienced this truth; but it has been experienced, too, by Venezuela, Nicaragua, Central America in general, Mexico, Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In recent years, apart from our people, Panama has experienced direct aggression, where the marines in the Canal Zone opened fire in cold blood against the defenseless people; the Dominican Republic, whose coast was violated by the Yankee fleet to avoid an outbreak of the just fury of the people after the death of Trujillo; and Colombia, whose capital was taken by assault as a result of a rebellion provoked by the assassination of Gaitán.[18] Covert interventions are carried out through military missions that participate in internal repression, organizing forces designed for that purpose in many countries, and also in coups d’état, which have been repeated so frequently on the Latin American continent during recent years. Concretely, U.S. forces intervened in the repression of the peoples of Venezuela, Colombia and Guatemala, who fought with weapons for their freedom. In Venezuela, not only do U.S. forces advise the army and the police, but they also direct acts of genocide carried out from the air against the peasant population in vast insurgent areas. And the Yankee companies operating there exert pressures of every kind to increase direct interference. The imperialists are preparing to repress the peoples of the Americas and are establishing an International of Crime.

The United States intervenes in Latin America invoking the defense of free institutions. The time will come when this Assembly will acquire greater maturity and demand of the U.S. Government guarantees for the life of the blacks and Latin Americans who live in that country, most of them U.S. citizens by origin or adoption.

Those who kill their own children and discriminate daily against them because of the color of their skin; those who let the murderers of blacks remain free, protecting them, and furthermore punishing the black population because they demand their legitimate rights as free men — how can those who do this consider themselves guardians of freedom? We understand that today the Assembly is not in a position to ask for explanations of these acts. It must be clearly established, however, that the government of the United States is not the champion of freedom, but rather the perpetrator of exploitation and oppression against the peoples of the world and against a large part of its own population.

To the ambiguous language with which some delegates have described the case of Cuba and the OAS, we reply with clear-cut words and we proclaim that the peoples of Latin America will make those servile, sell-out governments pay for their treason.

Cuba, distinguished delegates, a free and sovereign state with no chains binding it to anyone, with no foreign investments on its territory, with no proconsuls directing its policy, can speak with its head held high in this Assembly and can demonstrate the justice of the phrase by which it has been baptized: “Free Territory of the Americas.” Our example will bear fruit in the continent, as it is already doing to a certain extent in Guatemala, Colombia and Venezuela.

There is no small enemy nor insignificant force, because no longer are there isolated peoples. As the Second Declaration of Havana states:

“No nation in Latin America is weak — because each forms part of a family of 200 million brothers, who suffer the same miseries, who harbor the same sentiments, who have the same enemy, who dream about the same better future, and who count upon the solidarity of all honest men and women throughout the world…

This epic before us is going to be written by the hungry Indian masses, the peasants without land, the exploited workers. It is going to be written by the progressive masses, the honest and brilliant intellectuals, who so greatly abound in our suffering Latin American lands. Struggles of masses and ideas. An epic that will be carried forward by our peoples, mistreated and scorned by imperialism; our people, unreckoned with until today, who are now beginning to shake off their slumber. Imperialism considered us a weak and submissive flock; and now it begins to be terrified of that flock; a gigantic flock of 200 million Latin Americans in whom Yankee monopoly capitalism now sees its gravediggers…

But now from one end of the continent to the other they are signaling with clarity that the hour has come — the hour of their vindication. Now this anonymous mass, this America of color, somber, taciturn America, which all over the continent sings with the same sadness and disillusionment, now this mass is beginning to enter definitively into its own history, is beginning to write it with its own blood, is beginning to suffer and die for it.

Because now in the mountains and fields of America, on its flatlands and in its jungles, in the wilderness or in the traffic of cities, on the banks of its great oceans or rivers, this world is beginning to tremble. Anxious hands are stretched forth, ready to die for what is theirs, to win those rights that were laughed at by one and all for 500 years. Yes, now history will have to take the poor of America into account, the exploited and spurned of America, who have decided to begin writing their history for themselves for all time. Already they can be seen on the roads, on foot, day after day, in endless march of hundreds of kilometers to the governmental “eminences,” there to obtain their rights.

Already they can be seen armed with stones, sticks, machetes, in one direction and another, each day, occupying lands, sinking hooks into the land that belongs to them and defending it with their lives. They can be seen carrying signs, slogans, flags; letting them flap in the mountain or prairie winds. And the wave of anger, of demands for justice, of claims for rights trampled underfoot, which is beginning to sweep the lands of Latin America, will not stop. That wave will swell with every passing day. For that wave is composed of the greatest number, the majorities in every respect, those whose labor amasses the wealth and turns the wheels of history. Now they are awakening from the long, brutalizing sleep to which they had been subjected.

For this great mass of humanity has said, “Enough!” and has begun to march. And their march of giants will not be halted until they conquer true independence — for which they have vainly died more than once. Today, however, those who die will die like the Cubans at Playa Girón. They will die for their own true and never-to-be-surrendered independence”.

All this, distinguished delegates, this new will of a whole continent, of Latin America, is made manifest in the cry proclaimed daily by our masses as the irrefutable expression of their decision to fight and to paralyze the armed hand of the invader. It is a cry that has the understanding and support of all the peoples of the world and especially of the socialist camp, headed by the Soviet Union.

That cry is: Patria o muerte! [Homeland or death]

Source: Marxists Internet Archive