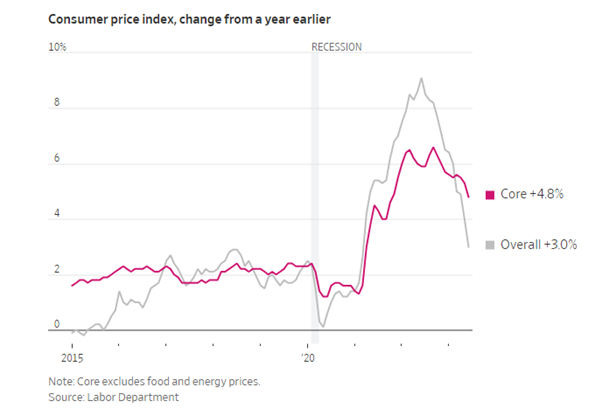

The latest measure of U.S. consumer price inflation for July actually showed an uptick in the year-on-year rate to 3.2% from 3% in June. That is mainly a result of comparison (‘base effects’, they are called) with a drop in the rate last July from the peak in June. Core inflation, which excludes food and energy prices, remained much higher at 4.7% yoy.

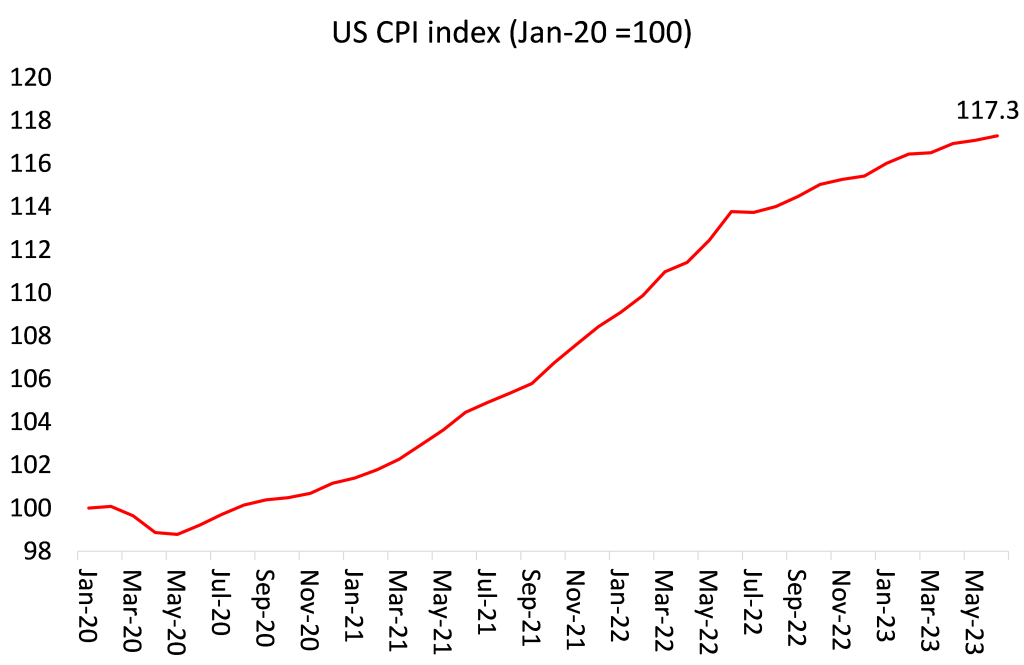

And remember, even if inflation were to fall further towards zero, prices since the end of the COVID pandemic slump are up 10-15% in most G7 economies, with those prices sheer to stay and probably rise more. Yes, the inflation rate is slowing, but U.S. consumer prices are 17% higher than they were at the beginning of 2021.

Inflation remains sticky in the U.S., and most G7 economies, which is why central banks continue to talk of further rises in their ‘policy’ interest rates. But the expectation is that national rates of inflation will come down (if slowly) over the rest of this year. Stock and bond market investors and mainstream economists are generally pleased and confident.

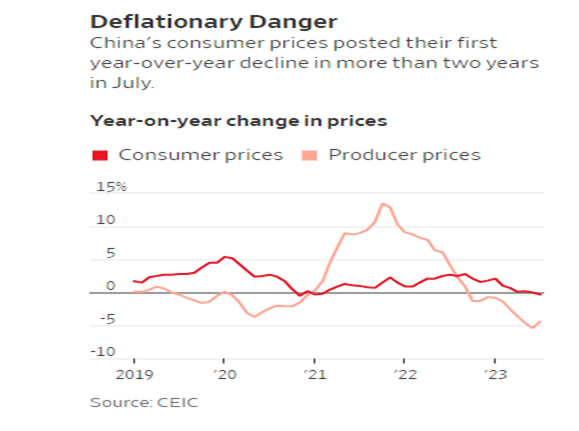

But how about having no inflation at all? That is the situation in China, where consumer prices fell in July compared to July 2022. This could be transitory, however. Stripping out volatile food and energy prices, so-called core inflation rose to 0.8% in July, the highest level since January, from 0.4% in June.

Deflation in China has been greeted by the China ‘experts’ as yet another sign that China is heading for a debt deflation disaster. They reckon that if the expectation of falling prices becomes entrenched, it could further sap ‘demand’, exacerbate debt burdens and even lock the economy into a debt trap that will be hard to escape using the stimulus measures Chinese policymakers have traditionally turned to. I have dealt with these arguments in a previous post, so I won’t go over the rebuttal.

And I am not sure working people would agree that having no inflation or even falling prices is such a bad thing, particularly as it means, in the case of China, that wages are still rising – so real incomes are going up, not down, as in the G7 economies. But then, capitalists companies like a bit of inflation to support profits and give them room to raise prices if they can – as we have seen.

China’s negative consumer inflation result was mainly driven by a drop in food prices from a year earlier when food prices were pushed up by extreme weather conditions. Prices of pork, a staple of Chinese dinner tables, plunged 26% in July from a year earlier. Vegetable prices also fell last month.

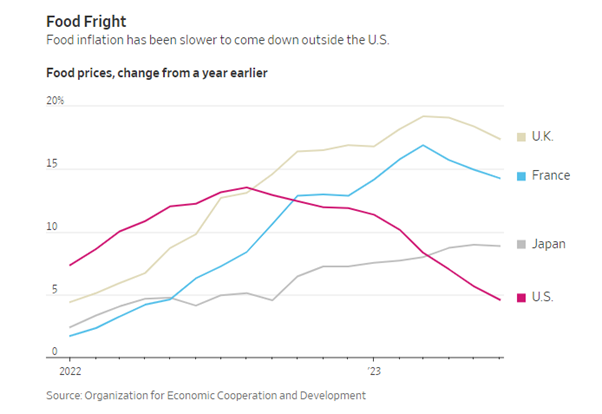

That’s not the case in the G7 economies. UK food prices rose 17.4% in the year through June, while Japanese prices were up 8.9%, and French prices were up 14.3%. In each country, food prices are rising much more quickly than prices of other goods and services. The U.S. has fared better, with food prices up only 4.6% from a year earlier in June.

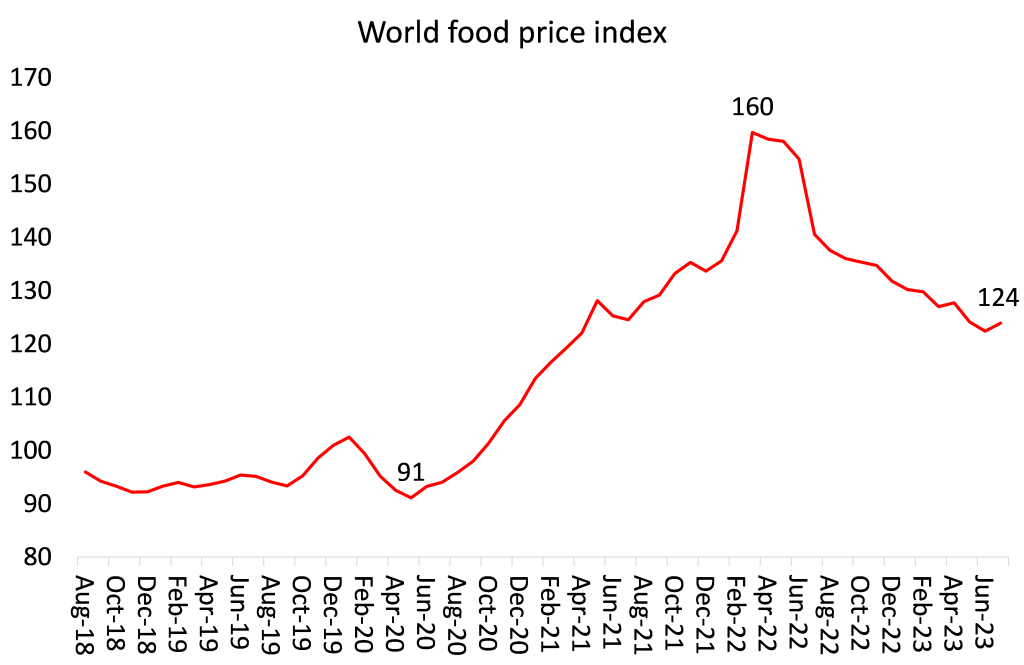

Food prices globally have fallen from the 50-year high in March 2022. But now it seems that the global food price index is turning up again, rising 1.3% in July from June, a second increase in four months. It remains 36% higher than it was three years ago.

The new rise in food inflation is partly driven by the collapse of the Black Sea grain deal between Russia and Ukraine to export their harvests. Last month, Russia withdrew from the deal and subsequently targeted the country’s food-export infrastructure with drone attacks on Odesa’s port facilities. Originally food price inflation was the product of supply chain blockages even before the Russia-Ukraine war began; now, it seems that those blockages could well return.

And then there is a further development: unusual weather patterns hitting harvests of a variety of grains, fruits, and vegetables around the world. July 2023 was the hottest month of all Julys on record. Climate scientists are saying that global warming to dangerous levels is coming upon the planet much faster than previously expected. “Adverse weather conditions, in light of the unfolding climate crisis, may push up food prices,” said European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde.

The impact of unfavorable weather has been most notable in India, where heavy rain has reduced the rice harvest and pushed food prices sharply higher. The Indian government last month imposed a ban on exports of certain types of rice, an echo of similar restrictions on the overseas sale of food staples that were announced by a number of governments as prices surged last year.

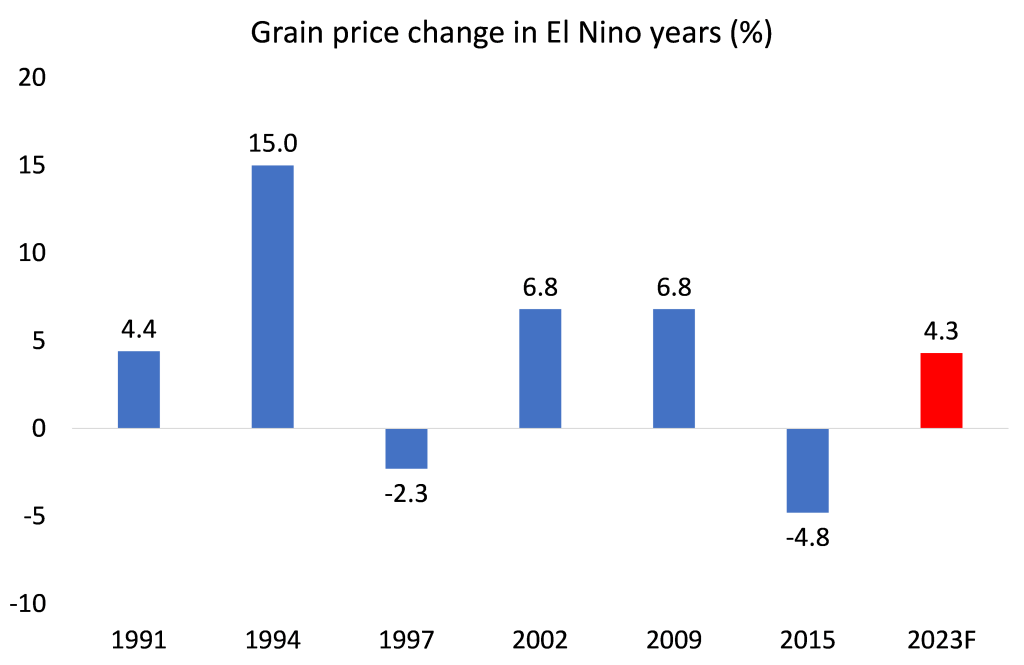

One additional risk to food supply is the strong natural warming condition in the Pacific Ocean known as El Niño, which can lead to changes in weather patterns and reduced harvests of some crops. The Australian government’s Bureau of Meteorology has issued an El Niño alert, saying there is a 70% chance that the climate pattern will emerge later this year. Previous El Niño periods have usually (but not always) led to rising grain prices. The ECB reckons that a one-degree celsius rise in temperature during El Nino historically raises food prices by more than 6% one year later.

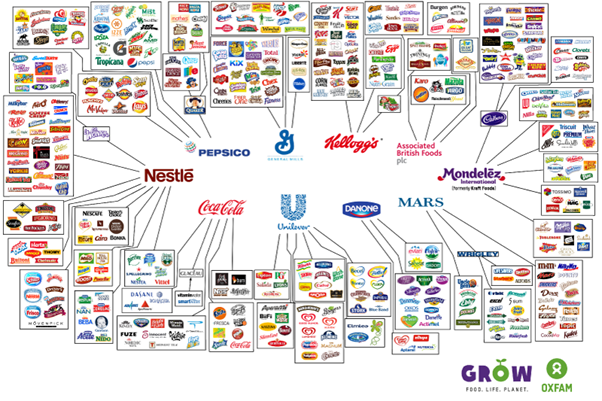

And then there are the food monopolies. Four companies – the Archer-Daniels-Midland Company, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus, known collectively as ABCD – control an estimated 70-90% of the global grain trade. They have been taking advantage of the food supply crisis by hiking their profit margins. Further up the food chain, just four corporations — Bayer, Corteva, ChemChina, and Limagrain — control more than 50% of the world’s seeds. From seeds and fertilizer to beer and soda, just a small number of firms maintain a powerful hold on the food industry, determining what is grown, how and where it’s cultivated, and what it sells for. Only ten companies control almost every large food and beverage brand in the world. These companies — Nestlé, PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, Unilever, Danone, General Mills, Kellogg’s, Mars, Associated British Foods, and Mondelez — each employ thousands and make billions of dollars in revenue every year.

Energy demand is relatively ‘elastic’ because there are rising alternatives fossil fuel production, and energy demand varies with global growth, industrial production, and trade. So when the world economy slows, and manufacturing goes into recession, as it has now, then demand for energy can fall back. That’s not the case for food. Billions in the poorest parts of the world need ‘food security’ as the cost of food takes up most of their incomes. And a fall in food supply will drive up prices much more than energy.

Indeed, it is food prices that will remain ‘sticky,’ and food inflation could well accelerate from here. Supply and international trade are in the doldrums. The IMF expects growth in global trade to slow to 2% this year from 5.2% last year. The World Bank and the World Trade Organization both forecast trade will grow by just 1.7% this year. Even a partial recovery in 2024 is predicted to fall well short of trade’s average yearly growth of 4.9% during the two decades before the pandemic. “Overall, the outlook for global trade in the second half of 2023 is pessimistic,” the UNCTAD wrote in a June report. The organization now forecasts the global goods trade to shrink by 0.4% in the second quarter when compared with the previous quarter.

This is a confirmation of the end of globalization since the end of the Great Recession of 2008-9 and the long depression of the 2010s. Trade growth no longer provides an escape when domestic growth is weak. Indeed, the world is entering a period of deglobalization led by the U.S. as imposes yet more measures on Chinese trade and investment with its ‘chip war’. The Biden administration has also kept in place most of the tariffs on goods from China and other countries implemented by the Trump administration.

This provides part of the explanation for the significant drop in Chinese exports to the rest of the world, according to the latest data. Overseas shipments from China slumped 14.5% in July from a year earlier, the steepest year-over-year decline since February 2020. Again, the Western experts see this as a sign of imminent collapse or stagnation of the Chinese economy. But it is more a sign of the weakening of economic growth, investment, and real wages in the G7 economies.

Indeed China continues to dominate global trade as it pushes deeper into markets other than the U.S. China’s overall share of global goods exports was 14.4% in 2022, up from 13% the year before the pandemic and 11% in 2012, according to World Trade Organization data.

A growing share of China’s exports are heading to regions including the Middle East and Latin America, reflecting strengthening economic links thanks to Chinese investment and its hunger for natural resources. China is also finding success exporting cheap electric cars and smartphones to emerging markets, edging out much more expensive Western alternatives. The country surpassed Japan as the world’s biggest exporter of vehicles in the first quarter of 2023.

The shift in export destinations also reflects worsening relations between China and the U.S.-led West that are crimping trade. Tariffs on a range of goods mean China accounted for around 15% of U.S. imports in the 12 months through May, down from more than 20% before Donald Trump hit a range of Chinese goods with tariffs in 2018.

Rising food inflation, falling trade growth, and a global manufacturing recession hardly make a recipe for an optimistic ‘soft landing’ for the G7 economies over the next year.

Source: Michael Roberts Blog